In Part One of this essay, I talked about reasons to be skeptical that generative AI is as revolutionary as it first appeared. I also argued that personalized chatbots are a narrow and expensive use of LLMs.

In Part Two below, I talk about reasons to be skeptical that universities will pay for generative AI at the prices AI companies are asking. And I argue that we should keep in mind that making decisions about technology this fall will happen during an unusually challenging moment for US higher education.

An affordable offering for universities to responsibly bring AI to campus?

The digital consumer economy runs on exchanging personal data for online services. I give Google my data for free. I use their products and services for free. Google makes its money by commodifying all the personal data it collects and using it to sell advertising services and other products. Even though Google kills great products that I love because they don’t understand what they do, I keep using its products because the effort to move all my email, documents, and other data somewhere else is just not worth it. They’ve got me.

Generative AI is complicating this dynamic, but essentially OpenAI and its competitors are following this well-worn groove by providing free or reduced-price versions of their transformer-based models in exchange for the data consumers give them. They have not figured out what they’re going to do, exactly, about the surprising fact that millions of people rushed to use ChatGPT. Once they had users, they had valuable data. Presumably, they have been using that data to make GPT-5 better and to figure out what products and services they can sell.

For ethical and regulatory reasons, educational institutions do not exchange data about students for services, so the ed-tech market works on a different dynamic with data.1 In order to access this market, technology companies must promise not to do anything with personal data other than what is absolutely necessary for the purpose of providing the agreed-upon service or product. Google and Microsoft agree to this because they want students to use their products and services after graduation. Each student using a product at school represents long-term value, either as a future customer or as a worker who doesn’t need to be trained to use its software.

This long-term value means technology companies sell their services to educational institutions at a price that, if not immediately profitable, at least returns enough in user growth and revenue to justify the expense. Apple (for hardware mostly), Google, and Microsoft have large operations dedicated to capturing the long-term value of student users by serving the needs of educational institutions that teach them. And now, OpenAI does, too.

It was not obvious to me that OpenAI would move in this direction. It seemed possible that they would focus on building the best foundation model and continue to offer consumers direct access to it. They could experiment with the GPT marketplace and sell access to developers as a service. Their partnership with Khan Academy creates perfect advertising for the education marketplace in the form of killer demos for all the underpants gnomes developing chatbots. This positions OpenAI as doing well by doing good through its support of an education non-profit.

OpenAI could have let everyone else figure out how to make products that schools would buy and simply avoided the hassle of negotiating privacy guarantees and the tricky work of price discovery. They could focus on renting the picks and shovels in the form of access to the best foundation model and let others pan the streams and mine the education hills.

Instead, OpenAI decided that direct access to students is valuable enough to spin up its own mining operation. Microsoft and Google were already there, putting generative AI services aimed at education in place last year. Microsoft Azure is how the University of Michigan led the charge in providing direct access to LLMs to its entire community starting last summer. Other institutions have been buying subscriptions in much smaller numbers in order to experiment. OpenAI hopes many colleges and universities will decide to pay for a subscription for every student and teacher at a list price of around $20 per month.

Just because Silicon Valley’s version of disruption is a myth doesn’t mean disruption won’t be coming this fall.

ChatGPT Edu is a bet that ChatGPT is a general purpose technology. Rather than power a variety of specialized GPTs or purpose-built educational tools, the bet is that ChatGPT will have enough utility as a general co-intelligence to be a universal teaching assistant or personalized tutor. It is a bet that enough teachers will use a chatbot assistant to make it worth their employer buying access for the whole faculty. It is a bet that universities will decide that a demand for equitable access—the argument that every student should get a ChatGPT subscription, not just those who can easily afford it—is more important than taking time to answer the question of its educational value.

They may be right. That makes sense if you believe the enthusiastic early adopters. As I have said before, I just don’t see this moving at the scale or the speed that OpenAI wants it to. So, I’ll take the other side of that bet for this fall.

Let’s think about the proposition. Multiply $20 per month by every student and teacher at your institution. Then, think about updating the university’s environmental impact statements with information about the energy required to use foundational models at that scale. Then, think about the labor practices being documented by this DAIR project. Then, think about the challenges of getting teachers to adopt generative AI at scale amid the ongoing reverberations of the homework crisis that has existed for years but, thanks to ChatGPT, is now in the spotlight. Then, think about how many students are going to want to use a subscription provided (and monitored?) by the University when they have been told that using ChatGPT is cheating.

OpenAI has not exactly blazed a trail in responsible corporate behavior. But even if you set aside the question of whether they will be good stewards of student data, there are more barriers to selling to higher education. They have to figure out the provisioning of student and faculty accounts, getting paid through university billing systems, and face the fact that any dean with a question can hold up a decision for months to get faculty input. Selling software to higher education is a different game than selling subscriptions to anyone with a credit card and an internet connection.

If the disillusionment about generative AI we are starting to see this summer really gets rolling this fall, how many colleges and universities will sign up for ChatGPT Edu? Even if the expectations stay up where the air is thin and OpenAI figures out how to navigate educational bureaucracies, how many institutions can afford to sign up enough users to make this worthwhile?

Disruption is a marketing term

Many AI enthusiasts and technology thought leaders have a very simple model for the way disruption works. A new technology is introduced into a sector of the economy. It fundamentally transforms how things get done, disrupting the organizations that manage the work. The new ways of doing things replace the old. When this happens, there are winners (OpenAI? Nvidia?) and losers (Google? Universities?). The dust settles on a transformed landscape where efficiencies have been realized, investments have been returned, and valuable optimization is unveiled to applause.

That’s not how any of this works. But it is an excellent story for the purpose of separating fools savvy investors from their money. That generative AI will disrupt higher education is an article of faith among a group of people who believed something similar about MOOCs just a decade ago. I haven’t seen much in the way of reflection from MOOC enthusiasts, so I don’t know how they account for its failure to disrupt higher education out of existence. My guess is that they moved on quickly without looking back. Reflection on the past isn’t really part of the Silicon Valley ethos.

MOOCs are the most recent example of an over-hyped educational technology. You might think it was universities who believed the hype and got taken for a ride. To understand what happened, it helps to recognize that disruption is not a marketing term for provosts and CIOs. It is aimed at savvy investors.

As what remains of EdX approaches bankruptcy and Coursera seeks revenue from their degree-seeking customers for a dark version of AI College, the structures now exist for universities to provide broad access to self-guided instructional materials to people for free. Look, I would much prefer a world where EdX had evolved into something that was truly for the public benefit, like Wikipedia. Or where Coursera invested more capital in providing free access to learners in the Global South. However, I’m thrilled that ModPo still offers the chance to talk online about Emily Dickinson and Walt Whitman to anyone with an internet connection.

Many of the universities involved in funding these endeavors, none of them exactly hurting financially, did quite well. Harvard and MIT cashed out just before edX’s stock price crashed, and the universities that invested in Coursera in 2012 must have been pleased with its IPO in 2021. If anyone got hurt, it was the savvy investors in Udacity, 2tor, and other MOOC start-ups who bought in at the lofty peak. Oh yeah, and the students who enrolled in SJSU+ or otherwise paid good money for worthless online credentials. Let’s not forget about the students.

Disruption happens

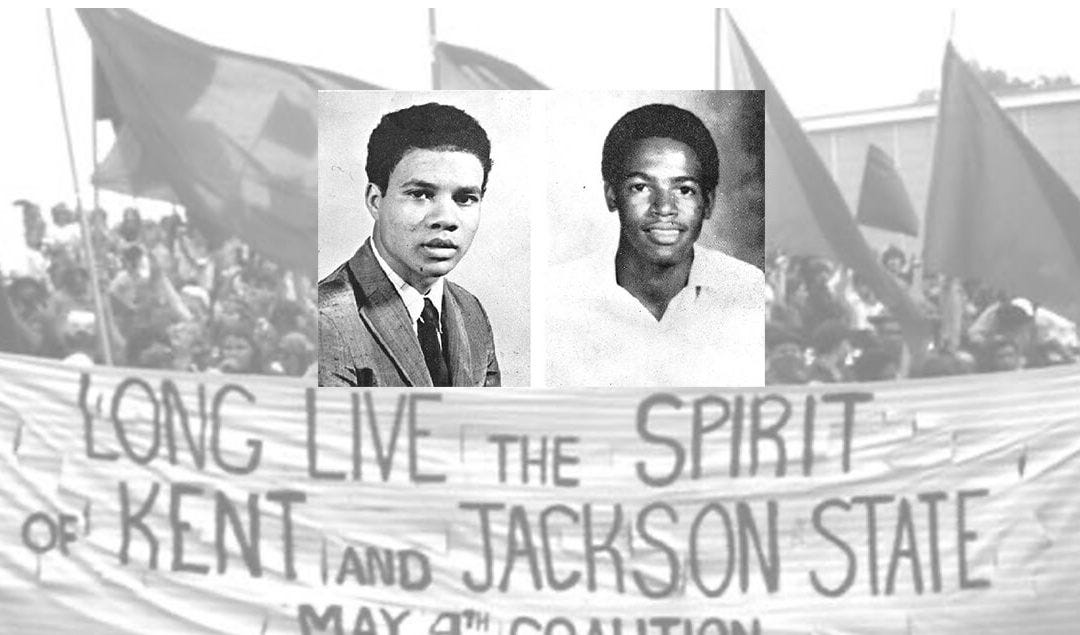

Just because Silicon Valley’s version of disruption is a myth doesn’t mean disruption won’t be coming this fall. We know something about what may happen because we lived through the student protests and the university leaders’ responses last spring. We recall what campus was like after the 2016 presidential election. Social conflict, never absent from college campuses, will feel intense this fall in ways that echo the late 1960s.

Perhaps university leadership will rethink the wisdom of sending police with firearms to clear out groups of students engaged in acts of civil disobedience. Perhaps 2016 is not the right frame for understanding this election and its aftermath. Even if this fall goes better than I fear, pressures for change are building.

It will not generate as many headlines or clicks as coverage of student protests, but there is a strengthening labor movement on campuses across the US. Although many faculty members prefer to think of their students as apprentices participating in guild traditions dating back to the Middle Ages, students are actually paid labor, essential to meet the demand for teaching on most US campuses. They perform entry-level educational work at low wages and frequently encounter unreasonable working conditions created by bosses who can flunk them out of school or destroy their careers if they get out of line. Lately, the National Labor Relations Board has been supporting these workers' rights to organize into collective bargaining units, and more students are taking advantage of the protections and wage increases that unions offer.

Generative AI is not driving this or other major conflicts on campuses. It is but one factor among many in the complex social dynamic that is always changing educational structures and methods. If you believe, as I do, that new tools do not determine how they are used and that human decisions, good and bad, determine the impacts of technology, then we should pause to reflect upon the social forces that will shape the decisions to come. What to do about generative AI will not be the most important question facing educational leaders this fall. Their capacity to focus on technology and decide how their institutions should respond will be limited.

The question of how much to spend on new technology will be answered by the same provosts and presidents who will approve the latest pay scales being negotiated by teaching and research assistants. At the same time, those leaders will decide which programs hire new faculty this year as they adjust budgets in the face of changing enrollments. These are not easy decisions. The number of eighteen-year-olds in the US is declining. Most students now understand that taking out loans to get an expensive master’s or doctoral degree is a luxury they cannot afford. Institutions will reckon with the reality that students have their own interests and beliefs when it comes to the value of their labor and what subjects to study.

As a history teacher, I like to remind people that colleges and universities have always been in crisis. As I do so yet again, I admit that the intensity of uncertainty, a feeling that this set of crises is different, has never been so palpable for me. Generative AI is only a small part of what concerns me about the fall, and like our leaders, teachers will have limited capacity to think about the new technology.

We will confront declining enrollments in the humanities in the same faculty meetings where we discuss new policies for the use of AI. We will figure out whether or how to teach with AI while we decide whether or how to hold class the day after the election. We will take a look at a colleague’s new LLM-powered virtual TA as we organize human TAs to do the work of leading discussion sessions and grading. We will prepare new graduate students to teach introductory writing classes as we wrestle with the fact that many undergraduates now have a tool that they believe makes writing obsolete.

This fall will not be an easy term. We haven’t had one of those in a while. Yet, if we find the capacity to act, this is a moment when we can still shape how our new tools are to be used in our classrooms. If we’re too busy, if this semester is too hard, then the moment will pass. The tools our students are using to shape their world are starting to shape our institutions. That’s how new tools change society, gradually and with little awareness of what we are creating with them. As Thoreau put it,

The man who independently plucked the fruits when he was hungry is become a farmer; and he who stood under a tree for shelter, a housekeeper. We now no longer camp as for a night, but have settled down on earth and forgotten heaven.

The transformer-based cultural technology that ChatGPT introduced to the world may not be all the enthusiasts claim it to be. But it is extremely effective at generating patterns of sentences that let students complete much of the academic work we assign them by clicking a button. Before we settle down in this world, we should think about the meaning of a liberal arts education in light of this development. Perhaps we should dedicate some time to deciding how we might adapt those traditions of thinking in response to these new tools.

Some think that we should build new tools to monitor students as they complete their academic work or go back to writing with pencils in bluebooks under the watchful eyes of proctors. I am looking for other, better ideas.

If I find them, I will write about them here. To have 𝑨𝑰 𝑳𝒐𝒈 delivered directly to your email inbox,

𝑨𝑰 𝑳𝒐𝒈 © 2024 by Rob Nelson is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0.

Please do share the “other, better ideas” you come up with! (In reference to college-level writing) As an English professor, I am one of those in the trenches trying to figure out how to teach writing and assign essays in this rapidly changing tech-and-education world. Thanks!

Absolutely. The conversation surrounding Significant Human Authorship and the logistical management of it in written compositions is something I would love to talk about with you all!