I started AI Log exactly a year ago today. I intended this essay to be my second post. In celebration of writing on the internet for a year, I finished it.

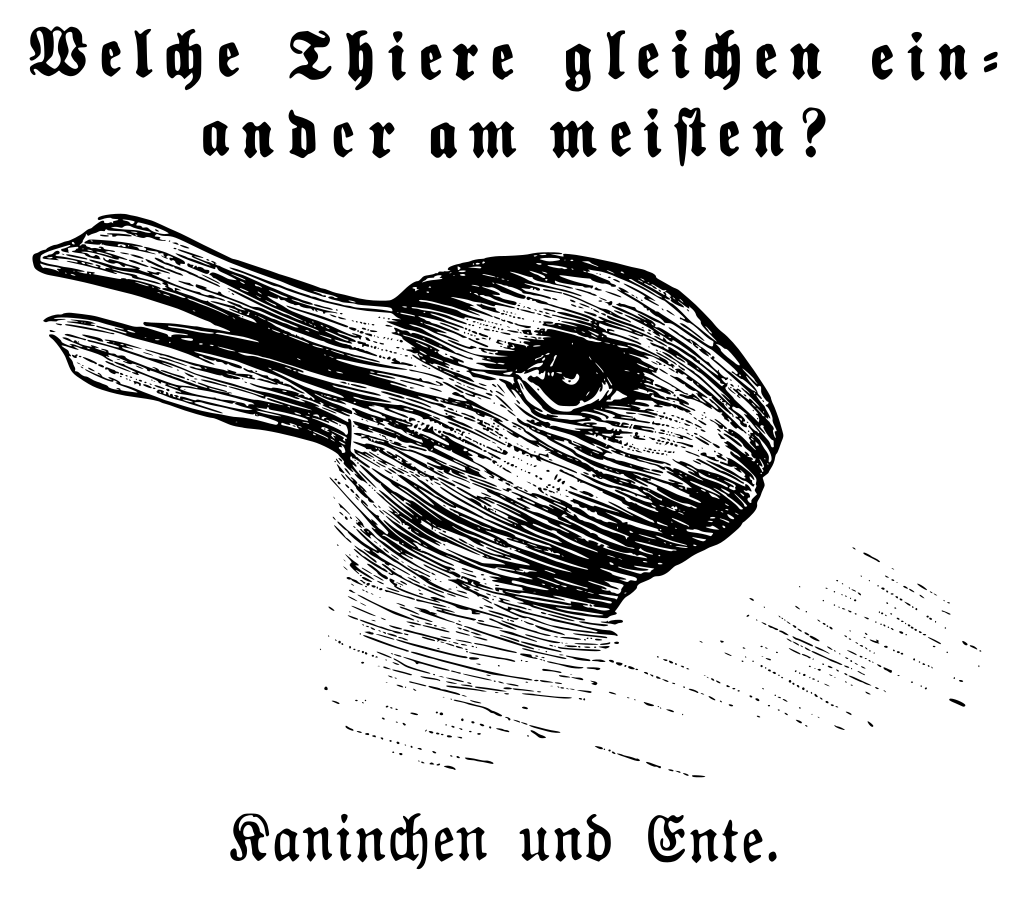

When I give talks at conferences, I use the “Rabbit and Duck” image to illustrate how we initially perceived generative AI as two things at once. Sometimes, we saw the Duck of Doom, who was going to take our job and give our students easy ways to cheat. Other times, the Rabbit of Glad Tidings appeared, offering to draft lesson plans or give us a head start on that stack of grading. The truth is that generative AI was both those things and neither. The AI Log is like the “Rabbit and Duck,” an ambiguous image meant to help move from our initial perceptions to understanding the social contexts and educational value of these new and complex cultural tools.

F. Scott Fitzgerald wrote that “the test of a first-rate intelligence is the ability to hold two opposed ideas in the mind at the same time, and still retain the ability to function.” This line is from an essay called “The Crack-Up,” in which he tells the story of his emotional breakdown. I’m not sure intelligence is the right word for this famous line. Next, he writes, “One should, for example, be able to see that things are hopeless and yet be determined to make them otherwise.” It seems to me, given the context, that he is writing more about wisdom than intelligence.

The AI Log aims for wisdom and is skeptical about the value of intelligence, at least as it is generally understood. I hope to help us get through our collective crack-up over the mix of doom and glad tidings driven by the excited and ambitious chatter about the idea that this latest version of thinking machines will render human creativity obsolete. Or, if not obsolete, at least forever changed by augmentation, a co-intelligence created by us that changes who we are.

The AI Log is about wisdom in the face of computational intelligence, a better name, I think, for what we have decided to call artificial. As we contemplate the latest advances in computational intelligence, I seek what Kenneth Burke called frames of acceptance, the more or less organized system of meanings by which a thinking person “gauges the historical situation and adopts a role with relation to it.” I seek frames that, as a friend of mine likes to say, are hopeful but not delusional.

Explaining the AI Log begins with a different log, much older and, in its time, quite famous.

Mark Hopkins and the Log

At an alumni dinner In 1871, James Garfield, then a congressman from Ohio on his way to becoming the 19th president of the United States, gave a tribute to his mentor, the President of Williams College: "The ideal college is Mark Hopkins on one end of a log and a student on the other." This idyllic image of a teacher and a student engaged in dialogue became a fixture in discussions about higher education for the next fifty years. As social life in the growing republic became more urban and industrial, gentlemen’s colleges like Harvard and Yale opened their doors a crack to a wider range of students and began grafting the new scientific model of the German research university onto its traditional curriculum.

Garfield’s nostalgic recollection of a small college experience expressed what felt like an important ideal to educated elites grappling with the social and technological transformations of the United States following the Civil War. The log is the perfect addition to the scene, invoking the log cabin that featured in US presidential campaigns throughout the nineteenth century. Garfield was the last of eight presidents who claimed to be born in a log cabin. It also looked forward to the nostalgia for rural and frontier life, anticipating the Little House that would make Laura Ingalls Wilder a household name.

Whether sitting on a log or in a professor’s office, the ideal of one-on-one conversation remains embedded in our aspirations for college learning, expressed in marketing materials promising individual access to famous faculty members and in the nervous encounters of first-year students with their teachers. That ideal was important for me when I started college. I got lucky. I found a mentor who helped me understand intellectual work by modeling for me how to talk and write about ideas and who read my work and took it seriously. I got lucky several times over in graduate school. Those conversations with writers whose books I purchased at my local bookstore shaped my dreams of what it means to write.

The setting for these encounters was not an idyllic forest glen. There was no log. There were chairs in book-filled offices and coffee shops. Actual places, not ideals. Reading literature and history, I learned to be suspicious of nostalgia. Stories of the past as somehow better than the present don’t hold up the light of clear-eyed cultural analysis. In the academy, the stories we tell about the past are now mostly about the people who did not attend Williams. They are about the people who lived in that forest glen before Ephraim Williams gave his name and fortune to found a college or about the people working in the factories and mills located on the other side of Massachusetts.

Historians have ruined history, at least the history that told stories simply celebrating the rich and powerful and the institutions they founded. Mark Hopkins and his log have lost their power to inspire. The past is no longer a place where we can safely project our ideals. We must look to the future.

Machines of Loving Grace

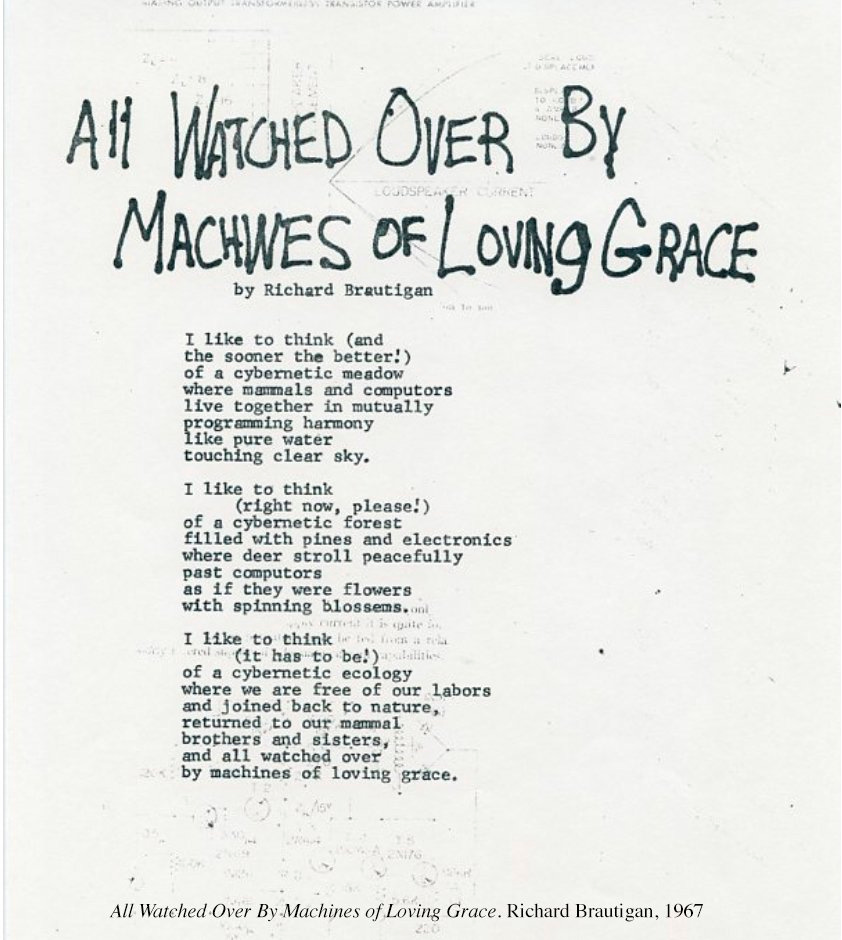

One influential story about the future is structured around a set of social ideas described by its critics as the California Ideology. This loose collection of ideas imagines idealized forms of computational intelligence, which create a world where we pursue knowledge and pleasure while being watched over by machines of loving grace.1

The path to Richard Brautigan’s cybernetic meadow, at least where education is concerned, begins with personalized tutors, much like Mark Hopkins and his log. In one version, the AI tutor becomes Hopkins, replacing human teachers with machines that never sleep or get frustrated. In another, AI replaces bureaucracy by gently automating the machinery of teaching and learning, freeing humans from institutional control. In both views, computational intelligence creates “a cybernetic ecology where we are free of our labors,” free of the work of grading and ranking, where we escape the ordinal society just as Garfied imagined Hopkins and his students escaping the industrializing, urban society developing around them.

In this story, the AI Log appears as a gift from the engineers, built to return us to the garden, where knowledge passes from person to person untroubled by the past. The image of sitting on an AI Log in a cybernetic meadow suffers the same delusion about history as Garfield’s story about sitting on a log in the Berkshire mountains. If the engineers have truly built a new thing under the sun, then history no longer matters. AI will make the crooked straight and number the wanting. We will catch the wind. Technology will solve human social problems.

This is not how technology changes society, of course. The history of the steam engine, the telegraph, and the dynamo say so. The social impacts of a transformative new technology are opportunities for great changes in fortunes, and they alter our lived environment, but they do not change the grammar of our motives. We are fixed by habit and language. Our social structures do not change easily or according to plan, even as goods and information move faster than the wind, and we work in light during the dark night. After they arrive, we barely note these transformations.

We have harnessed technology to create material abundance, but our politics is dedicated to guarding our share, fair or not. Billions of people hold computational devices of astonishing power in their hands yet use these devices in ways that are seldom wise. This is true of individuals and institutions.

The Crack-Up

Such pessimism attaches to any attempt at reform. The historical situation seems plastic as a new idea or new technology appears, but politics and habit harden around new social structures, narrowing the scope of change. In Garfield’s time, the grammar of schooling —the graded school, the elective system, assigning letter grades for courses measured by seat time—was put in place by the people who developed the common school and the research university. We treat this grammar as given, yet these structures are not even two hundred years old. However, cracks have appeared and seem to be spreading.

School attendance is declining and more public funding is going to private forms of schooling. The struggles of peer review, due to laws named after Donald Cambell and Charles Goodhart, along with terrible decisions about the financing of academic publishing, have created exactly what William James warned about in “The Ph.D. Octopus.” He wrote, “the institutionizing on a large scale of any natural combination of need and motive always tends to run into technicality and to develop a tyrannical Machine with unforeseen powers of exclusion and corruption.” The PhD Octopus and the “Rabbit and Duck” of computational intelligence are not a good combination.

The problem is not LLMs, which seem less impressive every day. Talking interfaces and culture generators, like pocket computers and the internet, will change many things and then fade into the background of our lived experience. The problem is that young people do not value the academic work their teachers assign them, and it seems that most teachers are unable to see that the problem is not the students. The use of technology to surveil and control learning environments is the wrong response. Computational intelligence did not create this problem, but unwise decisions about how to use it will only make things worse.

It is tempting to respond to this historical situation with jeremiads and Cassandra-like prophecies, but these have not been successful rhetorical modes for changing minds. The AI Log aims for something else. A Jamesian hopefulness in the face of uncertainty. A form of philosophical pragmatism that convinces engineers and teachers to build a better world today in our shared present, not one imagined in our distant future.

What is the 𝐀𝐈 Log?

Writing on the internet is a curious response to the threats we face, so it is worth asking what I hope to accomplish.

I write to think about mending the cracks in the foundations of institutions or trying to build new ones. I write to rethink the grammar of schooling and the grammar of motives of those who care about education.

I write about the social ideas of the nineteenth century, especially those of the intellectual tradition known as pragmatism, because I have been reading and writing about that tradition for decades.

I write for engineers, librarians, students, teachers, technologists, and other writers as we look together for ways to direct the use of technology that will shape and be shaped by our labor.

I doubt much wisdom will be found in the prophecies of technology barons. I doubt that comparing computational intelligence to human cognition will lead to a better understanding of either one.

Instead, I will look for wisdom in the more or less organized system of meanings we make together through sharing ideas to gauge our historical situation. We will find understanding in the messy and complicated institutions we build and perhaps rebuild to educate our children and each other.

The AI Log is not situated in a Massachusetts forest or a cybernetic meadow. It exists here and now in my attempts to gauge what is happening in educational institutions where my children learn and where I work and teach. I have it in mind as I see that things look hopeless, and yet believe that we should be determined to make them otherwise.

I hope to find understanding through the AI Log. I hope you will join me.

If you are curious to know more about 𝑨𝑰 𝑳𝒐𝒈, please visit the Brief Guide to AI Log.

𝑨𝑰 𝑳𝒐𝒈 © 2024 by Rob Nelson is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0.

There is another, more recent version of this story told by religious thinkers and cultural critics associated with Silicon Valley that imagines that computational intelligence will grow powerful and become a monstrous entity that will devour humans with the ferocity of deep-sea creatures attacking a wooden sailing vessel. This vision is interesting because so many people building computational intelligence are swept up by its power, but I also suspect it will fade as the ambitious chatter around transformer-based language models fades.

Great piece! So glad you are here and sharing your thinking. In many ways over the last year that it has become clear that we are running parallel tracks. Thankful for you, congratulations! 🎉

There is a lot to think about! One thing that sticks with me is the language we use within the context of this “new” technology.

Our human-created vocabulary shows our wariness, yet we have allowed this “thing” to become a part of our forever. Even the word “artificial” connates false, fake, not as good as the original. Yet, in some circles, we the people, are actively trying to see how AI can “stand in” for us…like in writing, grading, etc.

As a writer, do I want to write for artificially generated feedback, OR do I want to write so that a human will read it and be moved, inspired, informed?

The AI Log is amazing, Rob! Happy Anniversary! 🎉