Not that long ago, Marc Andreessen’s techno-optimism was the pole star by which opinion writers with something to say about technology set their course. Most headed away from the screedy manifesto while avoiding full-on pessimism about the social value of technological innovation. They aimed for a position in between, recognizing that while technological progress is overall a good thing for humans, it is a fallacy, as Matt Yglesias put it, “to infer that therefore all individual instances of technological progress are good.”

As most were picking apart what Henry Farrell called Andreessen’s “apostolic credo for the Religion of Progress,” Noah Smith and Vitalik Buterin restated techno-optimism as a more defensible set of ideas. Jay Cruz and Austin Kleon argued for techno-pragmatism as an alternative to both extremes, with Cruz suggesting that “techno-pragmatist embodies a balanced, reflective approach to technology — a mindset that acknowledges both its tremendous potential and its inherent risks” and then offering this formulation:

While techno-optimists herald innovation as the panacea for all human woes, and techno-skeptics warn of impending dystopia, the techno-pragmatist stands firmly in the middle, acknowledging both the promise and pitfalls of our era.

Both credit Dave Karpf who in his take on Andreesson, pointed back to his February essay, On technological optimism and technological pessimism. There he argues, “What we need, I think, is a robust, revitalized pragmatism.” Karpf arrives at his suggestion by reading James Carey’s 2005 essay, Historical Pragmatism and the Internet, finding that pragmatism “draws our attention to a different set of questions than either technological optimism or pessimism. It is a perspective that takes fragility quite seriously.”

That seems right to me, but incomplete. In Pragmatism, A New Name for Some Old Ways of Thinking, a collection of lectures published in 1907, William James provides the core philosophical arguments for the transatlantic collection of ideas known as pragmatism and offers it as a method for mediating between optimism and pessimism, a method that offers less a middle ground to stand upon than a direction of travel for those of us looking to create a more democratic future.1

Temperament as philosophical framework

James begins his first lecture with a joke that the history of philosophy is best understood not as a series of philosophical debates dating back to antiquity, but as “a certain clash of human temperaments.” He proceeds to show the truth of his joke by recasting arguments about philosophy and culture as occurring between these poles: “the ‘empiricist’ meaning your lover of facts in all their crude variety, and ‘rationalist’ meaning your devotee to abstract and eternal principles.” As James says, “No one can live an hour without both facts and principles, so it is a difference rather of emphasis.” This “simple and massive” contrast explains more about disagreements over ideas and culture than a detailed examination of ideas held by writers on opposite sides of a question.

James builds out this framework with a distinction between “tender-minded” and “tough-minded” temperaments.

For James, pragmatism mediates and reconciles these opposing temperaments, which necessarily includes an appreciation of the fragility of our beliefs and institutions. Here is Carey:

Pragmatism is a temperament or an attitude of mind which stresses not only human action and ideals, but also their inescapable limitations. It foreswears the promise of total solutions and wholesale salvation for piecemeal gains. Yet it acknowledges the reality of perceived losses, even when we risk our lives to achieve the gain.

If this sounds more like Wendell Berry or Ursula Franklin than pragmatism as you have usually heard it described, you are not alone. Critics of pragmatism have found it instrumentalist, optimistic, and technocratic, and far too accommodating of the capitalist economic and social order. In the words of Lewis Mumford, James’s thought carries the “smell of the Gilded Age: one feels in it the compromises, the evasions, the desire for a comfortable resting place.” Like many critics on the left, Mumford sees in James’s “persistent use of financial metaphors” a troubling willingness to entertain the possibility that capitalism is something other than a complete disaster for human freedom. This view of pragmatism is not wrong, just woefully incomplete. As Mumford himself says, many critics purposefully misread James as a representative American and pragmatism as simple-minded optimism.2

With all the preoccupations fostered by the Gilded Age, which were handed down to the succeeding generation, it was inevitable, I think, that James's ideas should have been caricatured. His doctrine of the verification of judgment, as something involved in the continuous process of thinking, instead of a preexistent correspondence between truth and reality, was distorted in controversy into a belief in the gospel of getting on. The carefully limited area he left to religious belief in The Will-to-Believe was transformed by ever-so-witty colleagues into the Will-to-make-believe. His conscious philosophy of pragmatism, which sought to ease one of the mighty, recurrent dilemmas of his personal life, was translated into a belief in the supremacy of cash-values and practical results; and the man who was perhaps one of the most cosmopolitan and cultivated minds of his generation was treated at times as if he were a provincial writer of newspaper platitudes, full of the gospel of smile.

In addition to distorting James’s ideas, critics miss what Carey emphasizes: pragmatism’s recognition of the ”real losses and real losers” in the processes of social change.

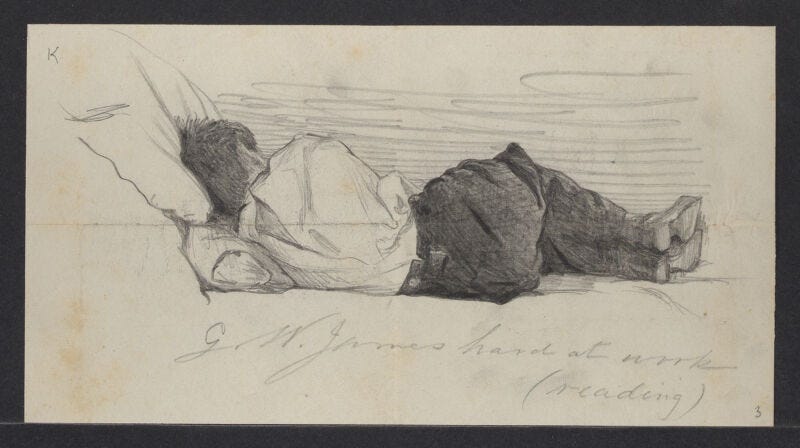

As Mumford says, this recognition was founded on James’s personal experience. As he pursued a medical degree at Harvard, James was hobbled by back pain and in a “permanent depression.” Traveling to Germany for research, he found himself living a “dead and drifting life” and contemplated suicide. Yet in the same year, while attending lectures on physiology in Berlin, he formulated a vision for his future, writing a colleague “that perhaps the time has come for Psychology to begin to be a science” and that there are “some measurements” being made “in the region lying between the physical changes in the nerves and the appearance of consciousness.” He returned to Harvard and began the research program that would produce The Principles of Psychology, a founding text for the new empirical study of the human mind.3

James’s scientific work informed his philosophical writing, but so did the temperamental necessity of finding meaning through action. Like Whitman’s poetry and Johnny Mercer’s song about accentuating the positive, James’s philosophy latches on to the affirmative, understanding that negative and in-between ways of being in the world can lead to despair.

A pragmatist turns his back resolutely and once for all upon a lot of inveterate habits dear to professional philosophers. He turns away from abstraction and insufficiency, from verbal solutions, from bad a priori reasons, from fixed principles, closed systems, and pretended absolutes and origins. He turns towards concreteness and adequacy, towards facts, towards action and power…It means the open air and possibilities of nature, as against dogma, artificiality, and the pretence of finality in truth.

You can see why James has never been popular among academic philosophers, and more important, you can see that pragmatism assumes we are in open and turbulent waters, not on solid ground holding a map. This attitude is especially important when we are confronted with something truly new–say electrical engineering in the early 1900s, the internet in the 1990s, or generative AI in 2020s. Uncertainty in the face of emergent machine capabilities requires new facts obtained through empirical investigation and new principles arrived at through reconsideration of existing truths.

Ethan Mollick is perhaps the best example of empirical inquiry today as he has turned One Useful Thing, into an open exploration of generative AI, writing about his experiments with the new tools, using the language of magic to make sense of some of its powers, and thinking in tightly focused ways about its social and organizational impacts. The reason Mollick is the essential writer of the past year is his pragmatical mindset. As others retreat to their prior assumptions about the value of technology or get lost in the thrilling metaphysical dangers of artificial general intelligence (AGI), Mollick turns toward concrete observation without losing sight of the larger questions we want to answer. When he takes a position–AI detectors don’t work; knowledge workers will use AI for work no matter what their bosses say; generative AI raises the level of the least skilled workers—it is based on observation and experiment, not conjecture. Mollick answers specific questions about how we should conduct ourselves in the face of the unknown capabilities of these new machines.

And Mollick is not alone. Academic journals, Substack, and LinkedIn have plenty of examples of writers trying out generative AI and reporting back from the jagged frontier. Many are earnest explorers trying to make sense of what they find and expressing anxiety and excitement about what they see coming. Some are con artists taking advantage of the uncertainty to sell AI Snake Oil. Others are managers of technology companies and their marketing teams, trying desperately to figure out how to sell the extraordinary and very weird tools their engineers have built.

Those engineers are an interesting bunch. The unstable social relations between the builders of the new machines and their mid-level corporate managers on one side and the capitalist investors/owners and their highly-paid CEOs on the other are reminders that we can no longer assume that everyone working in a corporate environment believes that maximizing shareholder value is the sole purpose of a corporation. Environmental, social, and corporate governance investing and the ethos of doing good while doing well are important contexts for the latest burst of techno-optimism. A pluralistic view of capitalism and the social good is an important part of the pragmatist tradition and its reemergence has frustrated the aging tech entrepreneurs facing skepticism about the social value of their life’s work and ingratitude from the rising generation. Where would we be without the internet? Why don’t the damn kids appreciate how lucky they are?

Part 2 of this essay is available here.

The usual history of pragmatism places its origins in some meetings in Cambridge, Massachusetts in 1872, and gives Charles Peirce equal billing with James. Louis Menand’s The Metaphysical Club tells that American tale well. I follow James T. Kloppenberg and James Livingston in placing pragmatism’s origins in the intellectual and social ideas flowing across the Atlantic. James himself credits his old friends Peirce and Chauncey Wright but places pragmatism’s entry into public culture in 1898 when James lectured at University of California, Berkeley. During the few years leading up to the 1906 lectures on pragmatism that became the book, James was deeply engaged with the writing of his fellow pragmatists—John Dewey, F. C. S. Schiller, and Giovanni Papini—and the controversies he and they were stirring up in philosophical journals circulating in the North Atlantic.

Lewis Mumford, The Golden Day, 1926, 191-192.

Robert D. Richardson, William James: In the Maelstrom of American Modernism, 2006, 85-94.

Really appreciate the cross-post and the comment. I'm working on at least one more piece about James, but then I'm hoping to turn my attention to some of the other figures in pragmatism. As I said in the comment on your Manifesto, I admire that you went big in that way. My approach is about digging around in their writing and bringing up nuggets that seem to cast light on problems we're seeing today.

I learn so much from these essays. I want to read more philosophy, but it always feels so daunting; you've made it feel accessible here, thank you