Dictionary meaning

A dictionary will tell you that to confabulate is to chat informally, to confer. This is what I do now. I confabulate with people about AI and education, people who work as academic advisors, application developers, bureaucrats, edtech executives, marketers, students, and teachers. Sometimes, I give talks about how AI is changing education and what we should do about it. I aim for confabulation in my public speaking and teaching, a sense that we are chatting together rather than that you are listening to pronouncements or deep insights. I want to talk with people, not at them.

My writing comes out of all this conferring, so the essays in AI Log are confabulatory. I aim to create a sense of conversation with my readers. William James was a master of this style of writing. Like all great artists, James makes the performance of something difficult look easy. In 1892, James turned his masterpiece, the dense, technical, two-volume Principles of Psychology, into Talks to Teachers, a series of informal-sounding essays about applying psychological concepts in the classroom. All his writing after Principles reads like talks given at conferences, teacher’s meetings, or to students. Most of them were.

Thinking of what writers do as confabulation encourages us not to take what we read on the page as final or definitive. We are just chatting, after all, through the process of writing and reading. Perhaps about some serious or important topic, say how AI is changing education. And, maybe, we will arrive at some important-sounding idea, or even some truth. If that happens, we should be careful. Fallibilism is in order. Truth-making is a tentative process, always partial and incomplete. Truth is the place to start a conversation, not end one.

Charles Peirce, best known as William James’s pragmatist pal, coined the term fallibilism, which he called “the doctrine that our knowledge is never absolute but always swims, as it were, in a continuum of uncertainty and of indeterminacy.” I think he captures something important, not just about how to talk about truth, but how to think and write in the modern world. Pragmatists believe in this doctrine even if they disagree over what it means to approach truth as a relation to reality, not as something fixed through discovery. How do you verify the truth of a statement when what is true can change over time?1

The attempt to keep that question in mind, to suggest we remain open to revising any statement of fact or truth, leads critics to dismiss pragmatism as wishy-washy. For good reason! It is irritating to disagree with someone only to have them change their position on pragmatic grounds. Pundits echo Peirce when they quote John Maynard Keynes’s famous line: “When the facts change, I change my mind. What do you do, sir?” What a cop-out.

There is no evidence Keynes ever said this. It appears Paul Samuelson confabulated different versions of the quote during the 1970s while talking with reporters, trying to give them a pithy explanation for why he had changed his mind about interest rates.

Semantic drift

The word confabulate began to take on this new meaning in the 1920s when psychiatrists used it to describe the behaviors of patients who, experiencing disordered or lost memories, made up experiences that had not occurred. People sometimes confabulate imaginary events from their past and are completely unaware that those experiences are not real memories. This meaning of the term confabulation drifted beyond psychiatry to describe when people with normally functioning memory confidently assert, and maybe even believe, that they have had experiences that they have not.

Experiences like reading a good line from a favorite author. As far as I know, Samuelson was never called on his confabulation, nor did he ever cite Keynes as having said this in an academic paper or book, though he did quote it in an essay in The Economist celebrating the Keynes Centenary. It is understood that sometimes a story or a quote is too good to check out.

Other times, though, veracity matters. Brian Williams ended his career as a nightly news anchor in 2015 when he confabulated an experience during the invasion of Iraq, repeatedly telling the story of when the helicopter he was traveling in was forced down after being hit by an RPG. I know from talking with my grandfathers, army veterans who served in WWII, that people sometimes exaggerate stories of their combat experience. Agreeing with reality is less important for veterans confabulating at the local American Legion or grandfathers telling stories. A journalist narrating the circumstances of his war reporting is different.

When ChatGPT or Gemini generates text or an image that is untrue, the result is treated more like Brian Williams than Paul Samuelson. The context of querying software means we expect an AI model’s outputs to be similar to those of news anchors or encyclopedias, not economists talking to reporters or old soldiers telling stories. Or, when my then four-year-old son explained how his lovey, Blue Dog, came to be tucked away in an oven mitt. Blue Dog’s disappearance sparked a three-hour search at bedtime and made for a grumpy evening. When the location was finally discovered, the confabulated explanation was that “Blue Dog must have climbed in the warm glove because he was cold.”

Confabulation and the future of AI

Skeptics like Ted Chiang and Gary Marcus prefer the term confabulate to hallucinate to describe this sort of behavior by large language models (LLMs). Like the words spoken by humans, the words generated by an LLM do not always agree with reality. Confabulating machines are completely unaware of this lack of agreement. Their nature makes them good at generating words that please their audience but unreliable when they try to answer questions, especially when they are too far removed from their training data.2

Hallucination means to perceive something that is not there. A human may report something they think is true based on a perception or experience. That’s not what Paul Samuelson or Brian Williams did. It is not what my son did. Their words were not based on a misperception of reality. They generated words in order to please an audience, words that suited the social purpose of being quoted in a newspaper, engaging an audience, or explaining their own behavior.

Another word for this sort of confabulation is bullshit.

Similarly, an LLM’s outputs are not based on perception or misperception of reality. LLMs apply probabilistic mathematics to language, and their outputs are reinforced with human feedback to try to ensure the words generated meet the expectations of their human interlocutors. The truthiness of an LLM output emerges in a social context of pleasing the person who asks a chatbot a question. ChatGPT and other foundation models with a chat interface do not hallucinate when they generate falsehoods. They generate words and present them confidently because that is what they do. That is their purpose. Those outputs are interesting, but it is unclear how economically or educationally valuable they are.

The impresarios who organize the markets for investing in AI technology confabulate. They believe that confabulation is part of their job. When Sam Altman tells us AGI is imminent or Elon Musk says we’ll soon ride in Tesla’s robotaxis, they are not lying. The future is uncertain and indeterminate. Yet, like Brian Williams’s war story or Sameulson quoting Keynes, their statements do not agree with reality. The future may be uncertain, but when Altman or anyone else involved with marketing AI makes a confident prediction, their words have nothing to do with swimming toward truth in the continuum of an indeterminant future. Their goal is to please and excite an audience already enthusiastic about whatever they imagine AI to be. Veracity matters not at all in the long con game being run by OpenAI. At least not to the people running the game.

When Altman and Musk confabulate the AI future using tropes from science fiction, they generate attention the same way P. T. Barnum did. Whether it is what you will see inside the tent or how AI will transform your life next year, the reality will not measure up to the hype. Yet, this does not hinder Altman and Musk. As they see it, their job is to gather a crowd, not to say things that agree with reality.

The job of a tech CEO is now apparently that of a carnival barker. You get people to open their wallets to see what’s behind the tent flap or the demo. What’s actually there has no real relation to the words the showman uses to describe it. Any disappointment with reality is the customer’s, or in OpenAI’s case, the investor’s problem.

Carnivals move on to the next town. What is happening these days with OpenAI and Tesla is perhaps best explained by that other famous not Keynes quote: "Markets can stay irrational longer than you can remain solvent."3

Bullshit

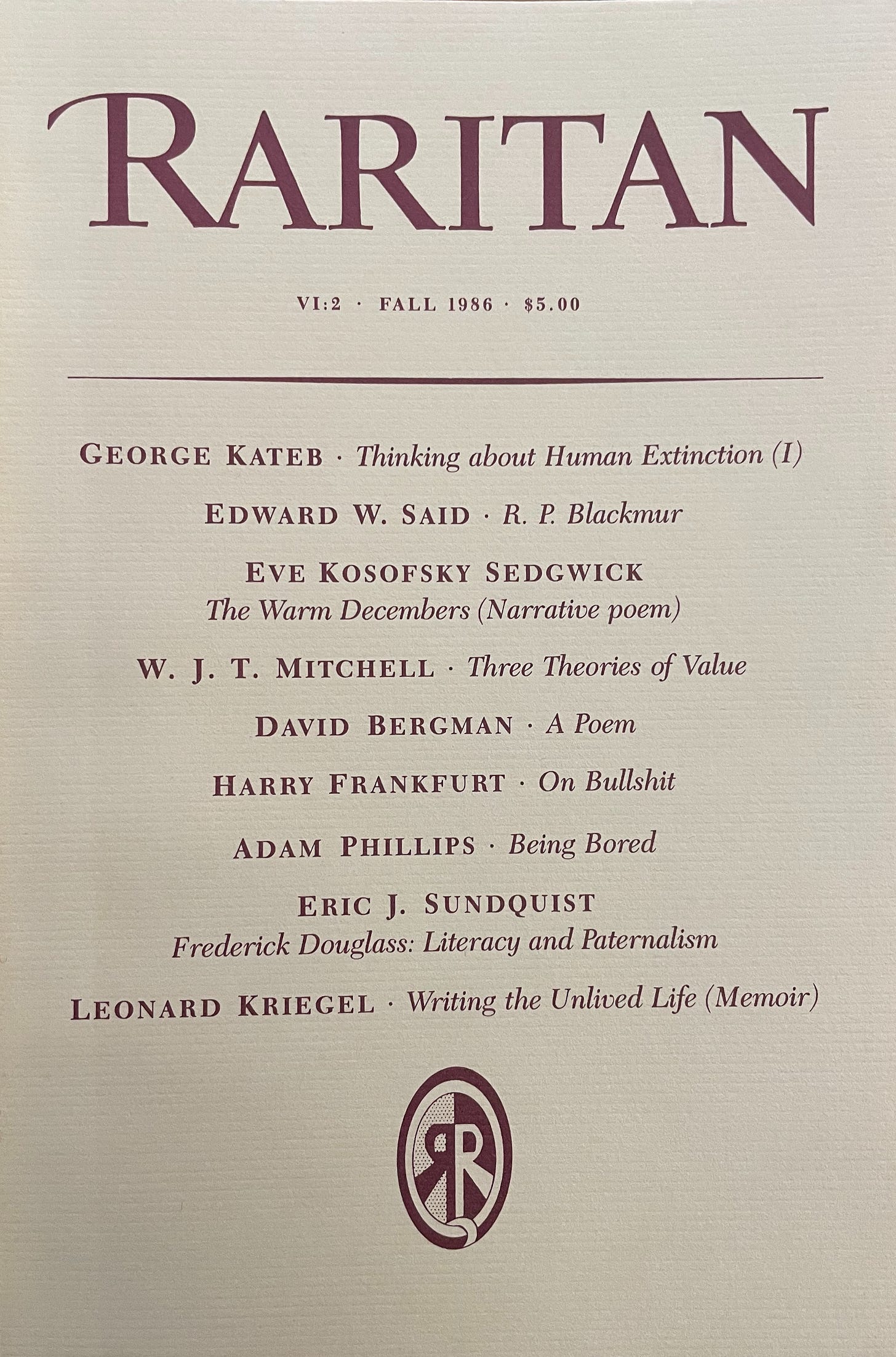

Another word for this sort of confabulation is bullshit. In the 1986 essay On Bullshit, Harry Frankfurt wrote that such language

is grounded neither in a belief that it is true nor, as a lie must be, in a belief that it is not true. It is just this lack of connection to a concern with truth—this indifference to how things really are—that I regard as of the essence of bullshit.

Bullshit, thus defined, is a useful term for understanding how the job of tech CEO has changed and how foundation models work as a cultural technology. In fact, this concept is useful for understanding the social problems associated with social media platforms and the internet generally. Cory Doctorow drew on Frankfurt’s understanding to coin the word enshittification to describe what happens at the end of a social media platform’s life, as delighting a platform’s audience in order to grow gives way to monetizing their attention by any means necessary.4

LLMs confabulate freely, regularly, and unpredictably because they lack connection to a concern with truth. This means they can’t replace dictionaries or encyclopedias, although thanks to Google’s decision to enshittify its search engine, it appears LLM outputs and other forms of digital slop might replace its internet search results. That makes me sad because Google started out by giving me the delightful experience of finding interesting and useful things on the internet and an excellent email service. Now I pay for Kagi and hey.com. Free is not free when it comes to Google.

An AI confabulator is not a dictionary or encyclopedia, though, like those two information tools, LLMs are the product of a great deal of human effort.

That, I think, explains something about ChatGPT’s popularity. It may not be able to answer your question, but neither can Google. If an LLM bullshits you as it chats, maybe it isn’t such a big deal. After all, a little bullshitting can be excused in the name of art or entertainment.

Sometimes, you want to punch up a story or give a line some colorful context. Keynes is not alone in having apochrypha attributed to him. Some of Albert Einstein’s, Mark Twain’s, and Yogi Berra’s best sentences are the confabulations of later writers reaching for a memorable phrase. Attaching a one-liner to a great man (nearly always a man) adds just the sort of context that makes for the perfect email tagline. “Be the change you want to see in the world” sounds more profound coming from Mahatma Gandhi.

There are times when you want to know the dictionary definition of a word, the date an event happened, or who actually said, “Predictions are hard, especially about the future.” Confabulators are not a good solution to these problems, no matter how easy they are to chat with. Even as post-training continues to reduce the amount of bullshit in their outputs, the potential of generative AI as a learning tool gets lost when we try to get it to act like an encyclopedia or an internet search back in the good old days. As Ethan Mollick says, LLMs are weird. Understanding their potential means embracing that weirdness, not trying to get them to behave like proper machines.

Handwriting on the walls

An AI confabulator is not a dictionary or encyclopedia, though, like those two information tools, LLMs are the product of a great deal of human effort. A digital printing press that extrudes lumps of text made from the repository of language that is the internet is unreliable, but then so were the devices Johannes Gutenberg built in the fifteenth century. In 1492, another Johannes, the Benedictine abbot, scholar, and cryptographer with the byname Trithemius, concluded his essay “In Praise of Scribes” with this observation:

Printed books will never be the equivalent of handwritten codices, especially since printed books are often deficient in spelling and appearance. The simple reason is that copying by hand involves more diligence and industry.

Trithemius was wrong about the relative deficiencies of print, at least in the long term. But he was right that writing by hand would remain valuable in the age of print. Few people copy out long passages by hand anymore, though my elementary school teachers saw value in that exercise. Despite my terrible handwriting (I blame those teachers), I write the beginning of my essays using a good pen on quality paper, not for the sake of accuracy or efficiency, nor as Trithemius believed, because words “written on parchment would last a thousand years.” I write by hand because it engages my mind differently than typing on a screen. Reading a printed book has a similar effect.

Just as the new cultural technologies of generative AI threaten long-standing practices embedded in schools and colleges, movable-type printing machines threatened the practice of hand-copying knowledge. And yet, there are still monasteries and universities. There are even scribes today, though the job is a bit different.

Trithemius urged his audience to value the cultural labor of scribes. Today, many of us who teach writing and the humanities are urging our audience to value print-based forms of reading and writing. We fear, rightly, I think, the social dangers of a new cultural technology. After all, the printing press was deeply entangled in the religious wars and revolutions that followed its creation.

Trithemious could no more predict what was to become of scribing in the age of print than we can predict what will become of writing and research in the age of digital media. Fallibilism seems the wisest way to approach the intellectual world we are creating with the internet. That includes not drawing firm conclusions from analogizing transformer-based confabulators to the printing press.

Confabulating our future

According to one of the first English dictionaries, A table alphabeticall (1604) by Robert Cawdrey, confabulate means “to talke together.” I want to preserve this original sense of the word, even as it is increasingly used as a synonym for bullshit. I suspect whichever writer coined the term in the sixteenth century was looking to describe human verbal interaction at a moment when engraving, etching, and printing were expanding the range of what art could be produced mechanically. Maybe the word confabulation can help us think about what it means to use generative AI to produce cultural artifacts out of the dank soil of the internet.

Like establishing authorship when someone uses an AI output to produce the first draft of an essay, there is no clear separating the different definitions of confabulation. Its meanings are a continuum. Bullshitting among friends can be fun and harmless and is, perhaps, essential to the informality of chatting. Not so when bullshit is relied upon to provide medical care or used to separate fools from their money. Context matters.

The educational value of confabulation becomes clearer if we let go of the idea that learning is an efficient process by which information gets transferred from expert to novice, that a student’s mind is an empty vessel to be filled with knowledge or disciplined through meaningless, repetitive tasks. That’s not how learning works. A machine that simply gives an answer does not teach. Yet, application developers trained to think in terms of optimization build AI learning tools that assume a straight line can be drawn directly through the messy, uncertain reality of how humans come to know the world.

Around the same time Blue Dog tucked himself in the oven mitt, I rediscovered the ancient teaching strategy of playing the hapless, dumb dad who needs to be taught the basics. I would pretend that I forgot how to put on socks, flush the potty, or tie my shoes. My young kids found my confabulatory performance of cluelessness hilarious and proudly took it upon themselves to correct my errors. Docendo discimus. By teaching, we learn.5

We need to keep this lesson in mind as we consider the educational potential of generative AI. A machine need not be perfect, or even particularly good at something, to be educationally useful. There are advantages to using fallible teaching machines as long as we keep in mind their specific forms of fallibility and understand them as tools to be used by humans rather than as human replacements. The purpose of an educational tool is to make us think, not think for us.

We already have cultural tools that we use to verify facts or look up what people already know. And sure, putting a better natural language interface on those tools is neat. But what happens when that makes them less reliable? Then, I think, they become a different kind of tool. To what educational purposes can we put an AI confabulator? I am not sure. Let’s confabulate.

AI Log, LLC. ©2025 All rights reserved.

I use the phrase “agree with reality” throughout this essay. It was a favorite of William James, though I don’t know if he was the first to use it. I think it captures something important about the complicated relationship between our lived experience and the language we use to describe that experience.

One of the ambitions of this blog is to contribute to a renewed engagement with James and other nineteenth-century writers because I think their ideas are relevant to social questions raised by generative AI. To my amazement, the essay On Techno-pragmatism remains one of my most read.

There is sharp disagreement among experts about how LLMs arrive at their outputs. This two-part essay by

explores these debates in ways I found refreshing and illuminating. Do they have emerging “world models” comparable to the ways humans make sense of the reality they experience, or are LLMs simply using a “bag of heuristics” that allow them to make predictions that happen to agree with reality some of the time? I don’t think we know for sure, but my reading of James and Peirce suggests that we have created machines with impressive heuristic capabilities that have little in common with the human mind.Is this time different? Whether meme stocks, meme coins, and related bullshit finance represent a permanent change in how financial markets work is a real question. As someone who reads a lot in the nineteenth century, I think this all looks familiar. The rhythms of boom and bust that started in the US with the Panic of 1819 will continue. It may feel as though there is no ocean floor or sun behind the clouds as investors swim in “the continuum of uncertainty and of indeterminacy.” Yet, I think it may well be that Warren Buffet will die as the world’s wealthiest person.

Given Musk’s leading role in the kleptocratic power moves taking place in Washington, thinking in terms of markets may seem too limited. But the point applies to politics, too. I am hopeful that those who aim at money or power by actively disregarding reality will eventually pay a price.

Bullshit pre-dates artificial intelligence. P. T. Barnum confabulated piles of it to sell tickets to see the Feejee mermaid and other entertainments. William Randolf Hearst sold piles of newspapers and a war the same way. Thomas Edison bullshitted his way through the “war of the currents” only to lose out to George Westinghouse when alternating current systems turned out to be a safer, more sustainable method of generating and distributing electricity. There may lessons in there somewhere for how we think about AI today.

That said, I think bullshitting about technology and science took on a greater intensity with the internet, starting, maybe, with Dolly the sheep and the inevitability of human cloning.

is onto something in this essay and his current book project.Seneca often gets the credit for that line, but the phrase does not appear in any of his known works, so it was likely confabulated by later writers.

Confabulous

Love this piece, Rob. Lots of magic here. Yes, let’s stretch language to fit this new reality. She’d these mismatched, misleading words as we stretch.