To understand how Mike Kentz is implicated in this, click here.

The toxic role of science fiction

In the original Terminator (1984), Arnold Schwarzenegger plays a killer robot sent back in time to kill Sarah Connor, the mother of humanity’s future leader. In the sequel, Schwarzenegger plays the hero, still a killer robot, but now he is on humanity’s side. The other side is evil AI, as represented by Cyberdyne Systems and personified by the T-1000 killer robot, which mechanically carries out its instructions to murder Sarah and anyone who gets in his way. The T-1000 cares about nothing except its goal.

Terminator and its sequels are probably the best-known parables illustrating the future AI doomers like to imagine: Humans build AI. Then, AI develops a goal like making paperclips or murdering all humans. Then, an unstoppable superintelligence pursues that goal with maximum efficiency. Oops!

Charlie Stross’s exploration from a year ago in “We’re sorry we created the Torment Nexus” is my favorite account of the role science fiction has played in the development of AI.

Speaking as a science fiction writer, I'd like to offer a heartfelt apology for my part in the silicon valley oligarchy's rise to power. And I'd like to examine the toxic role of science fiction in providing justifications for the craziness.

Thanks to the reading and movie-viewing habits of tech barons and the computer science majors they hire, Silicon Valley has become obsessed with imagining variations of the Terminator backstory. Critics point out how talking so much about the risk of human extinction in the future conveniently distracts us from the Silicon Valley’s shenanigans going on right now. No doubt that’s true, but many p(doom)ers are drawn to visions of the AI apocalypse because it lets them tap deep historical reservoirs of millenarian religious feeling that their rationalist beliefs would deny. Henry Farrell who writes

is quite good on this.Disentangling Silicon Valley’s strategy of getting its way using sleight-of-hand illusions from their varieties of religious experience seems less urgent than shifting the discourse back to what’s happening today, including asking why certain stories about AI get told and for what purposes.

For starters, let me suggest that stories about AI could be different. How about an imagined future where we just say no to anthropomorphic machines, especially ones designed to take care of us. Or teach us. Or murder us. Why not tell stories about thinking machines that emphasize their toolness rather than imagining AI models that only desire to become human, or to kill us all?1

Murderbot futures

While we wait for the sci-fi genre to swerve in the direction of my preferences, let’s talk about an actual existing alternative to telling and retelling stories of the singularity. How about an imagined future where the social order mostly remains in the hands of human oligarchs, and they, not a fantastical superintelligence, develop corporate entities that own the technology to take humans to the stars? In this story, humanity survives. Yay! Mostly in a dystopian future run by a handful of unaccountability machines generating profits for an elite few while making most people miserable. Boo!

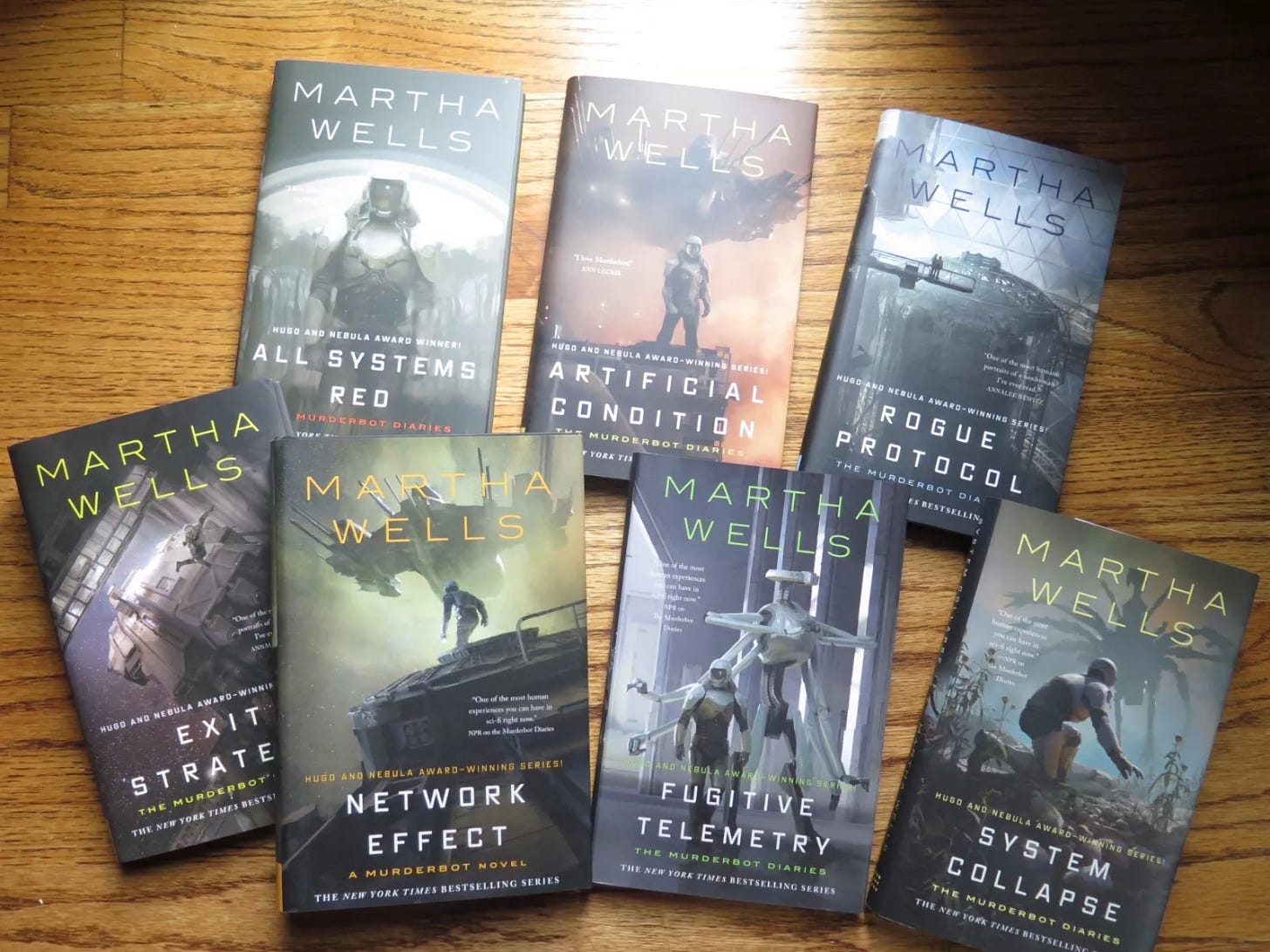

That’s the backstory of The Murderbot Diaries by Martha Wells. This killer robot, who gives itself the name Murderbot, is like the Arnoldbot in T2 in that it throws off the chains written in its code and resists the designs of its corporate masters. The process of resistance and self-creation leads to complicated feelings in Murderbot. Imagine Frantz Fanon and Anushka Shetty had an orphaned neurodivergent teenager who announced its preferred pronoun was “it” and ran away from home to explore its identity.

To be clear, Murderbot is not entirely a machine. It’s a hybrid, a consciousness born from some far-future version of Neuralink that actually works. In fact, the backstory is that Neuralink becomes a dominant technology of the future; only the galaxy-wide monopolies who own the IP torture human/machine hybrids for their research instead of limiting the torture to non-human primates, as seems to be Neuralink’s current practice. And, since the technology actually works, the bad guys profit by licensing these hybrid models out for security roles. And, of course, murder.

This dystopian future is the context for a marvelous exploration of an emerging consciousness in an individual self whose brain is part human and part machine. Murderbot’s self-creation happens through awkward interactions with friends, violent resistance to unjust authority, and watching soap operas about humans being terrorized by Security Units (the official name for murderbots). You can see why The Murderbot Diaries was picked up for development as a TV series.

You can also see why I chose it as a contrast to The Wild Robot and to Mike’s invocation of The Jungle Book by Rudyard Kipling, best known, perhaps, as the author of these lines.2

Take up the White Man's burden—

Send forth the best ye breed—

Go bind your sons to exile

To serve your captives' need;

To wait in heavy harness

On fluttered folk and wild—

Your new-caught sullen peoples,

Half devil and half child. Go send your sons to exileMike’s insight is that most stories about AI robots are like Terminator and Murderbot. The bots “serve as assistants, saviors, villains, or characters in need of help.” Their identity as conscious beings is established not through reason but emotion. These bot characters are all “driven or motivated by their connections to other human beings.”

The Wild Robot’s removal of humans from the context of identity formation is a departure. And though the move is as old as Aesop's Fables, Mike is onto something when he says that limiting characters to animals and bots in this story has particular importance at this historical moment.

As we see more human-like AI characters in our movies, TV shows, and books, we're subtly being conditioned to view real AI systems through a more human lens. In the film, Roz finds she is only able to “complete her task” by finding love inside of herself, a uniquely human characteristic.

How reassuring it is to imagine AI models will have a natural tendency to develop emotional attachments! These fantastical stories about AI models becoming conscious in human-like ways offer exactly what AI models themselves cannot: emotional meaning.

Whether it is a chatbot named after Daenerys Targaryen or one that is trained on the personal data of your dead loved one, humans bring meaning to the outputs of transformer-based AI models. Suspending disbelief when talking to an LLM is a crucial part of the cultural experience, not so different from identifying with characters in a novel or film. And yet, think about how the experience of chatting with an LLM is structured by the stories we have been told about the Maschinenmensch, HAL, the Terminator, and Her.

Storytellers provide what technologists cannot: a compelling backstory with rich emotional context for humanizing AI. Storytellers also construct worlds that comment critically on our own, even though readers don’t always notice or care. Wells’s dystopia is populated by corporate entities managed by status-maximizing humans morally blind to the effects of the creative destruction they inflict on fellow humans. In its transition from a tool of violence to a conscious being, Murderbot resists those entities and, in so doing, entertains the reader in ways that raise questions about our current political and economic order.

Stross says that the tech barons took the imagined world of the Terminator films and similar stories “at face value and decided to implement it for real.” Wells imagines a future where the villain is unchecked techno-capitalism, a future that seems more probable than the sudden appearance of a superintelligence who wants to murder humankind. Given our current political situation and the slowly dawning realization that near-term AGI is just some weird religious thing, the future of The Murderbot Diaries is worth thinking about so that we can work to prevent it.

Roz, the robot in The Wild Robot, lives in a different kind of future. She is the product of Universal Dynamics, a corporation that is the reverse image of Terminator’s Cyberdyne Systems. Universal Dynamics apparently builds AI robot caretakers with the capacity to love all living creatures. Given the choice, I’d take the good intentions of Roz’s makers and the world of Peter Brown’s novel. However, by leaving out the humans, The Wild Robot ducks the important question of how intelligent machines and humans might co-exist. And maybe such tales are the best we can do when it comes to young humans.

Murderbot is no children’s tale. It doesn’t address the problem Mike poses: how should stories introduce small humans to the world we are actually making with AI? I’ve not read it, but the sequel, The Wild Robot Escapes, sends Roz to the city. It’s next on my list. What other children’s books I should be reading in preparation for the next round?

Keep an eye out for Mike’s next move on AI EduPathways.

𝑨𝑰 𝑳𝒐𝒈 © 2024 by Rob Nelson is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0.

For an excellent take on Heidegger and “toolness” or “tool-being” in this context, check out this post on AI agents from

. Given all the excitement over the agentic aspects of the latest AI features, this is a key insight:“When we speak of AI agents, we risk anthropomorphizing these systems, attributing to them levels of agency and autonomy they do not possess. This misrepresentation can obscure the reality that AI, no matter how advanced, remains fundamentally a tool designed to augment human capabilities, not replace them. I would argue that it has never been more important to keep a tight grip on this fundamental insight.”

Nick’s right. Automaticity is not agency. Combining natural language interfaces with automation does not produce “glimmers of consciousness.” Let’s just not.

Kipling is also the author of Just So Stories for Children. Audrey Watters has some fun on her blog, rounding up “just-so” stories about AI.