Meet Ed. Is our happy chatbot future already here?

Lessons from the rollout of the new chatbot for the LA Unified School District

You’ve likely heard some version of this line attributed to William Gibson: “The future has arrived – it’s just not evenly distributed yet.” The process of distributing the future is an interesting way to think about what has been happening with generative AI and education over the past year. The initial moral panic about ChatGPT has subsided (mostly) and campus discussions about AI these days feature teachers and researchers doing interesting things with the new technology. The slow machinery of university governance has begun to crank out policies and guidance about its use. More teachers than not seem to have some direct experience using generative AI.

Many would agree that generative AI has potential, even if they are not sure what for. The folks who have not engaged, those who don’t go to AI meetings, who are too busy or quietly fearful of whatever is happening, are coming to generative AI through a side door. They press that new button labeled something AI in the corner of an app they already use or ask a friend to show them what they are working on, and suddenly, they’ve used it or seen it in action. These individual encounters shape the adoption of new technology far more than any organized adoption program, and certainly more than emails from executive leadership or reports from the Committeee on the Thing that Needs to be Reported On.

The biggest problem facing most institutions is how to put the technology into the hands of teachers and administrators who want to try it, and even that seems like it is being solved, at least on campuses that can afford it. That’s the point of Gibson’s line about the future: the rich can afford it. As I have argued, what we need in these early days is small, incremental projects that bring educators together to apply participatory design thinking to experiments that teach organizations how best to use these new tools. We also need to find ways to ensure that implementing generative AI does not extend or exacerbate existing inequalities. What don’t we need? Top-down implementations that do not consider the needs of educators and students.

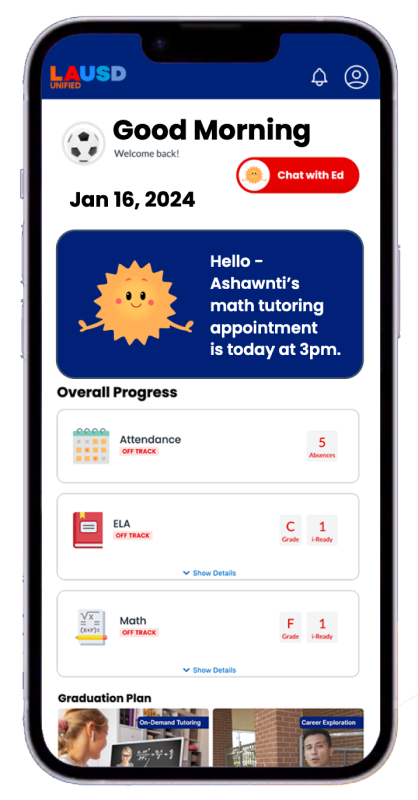

This forms the backdrop for the announcement of Ed, a chatbot who will “serve as a student advisor, programmed to tell its young users and their parents about grades, tests results and attendance — while giving out assignments, suggesting readings and even helping students cope with nonacademic matters.” First, I’d like to thank the Los Angeles Unified School District officials for using a male name. It was a bold decision to swim against the current conventional wisdom that all chatbots be gendered female. Seriously, thanks. Second, I’d like to express my condolences.

Rolling out any new splashy software is a tricky business, and I’m sure this one has left scars on school officials and technologists. The LA Times is fairly neutral in its article about Ed, but this feels like the beginning of a Clippy-level disaster. The rollout even featured a performer in a full-body Ed costume because….? The prepared talking points from public officials boil down to It’s a game changer that prepares students for the future! The article quotes a few skeptics saying the usual skeptical things and points out the significant problems facing the district that Ed does not address. The unanswered question is what problem are they trying to solve here? To be fair this could be asked of almost any generative AI product, but this one involves a six-million-dollar contract for a school district facing budget headwinds. I suspect Ed is the first of many similar AI announcements as projects conceived at the peak of chatbot excitement bear fruit. Does anyone doubt that soon there will be a happy apple logo smiling her way through another school district rollout event later this year?

It is not hard to imagine how LAUSD got to last week’s announcement. District executives, pressured by their board or excited about ChatGPT, told their staff to get moving on this AI thing. The result is a chatbot guardrailed up to its non-existing eyebrows and trained on data already publicly accessible on the LAUSD website. Ed is not a personalized tutor….its personalization consists of showing a student their report card and attendance record (I’m sure that’s fine, right?) so its advice mostly consists of referrals to existing services and websites. In a preview back in August, Superintendent Alberto Carvalho suggested that Ed would be part of the district’s Individualized Educational Program that supports students with a disability, but there is nothing on the LAUSD website or news coverage that suggests the chatbot is actually providing individualized advising.

Maybe Ed won’t be all that bad

I suspect Ed will spend the rest of the school year disappointing optimists and providing ammunition for skeptics. Future headlines and follow-up articles will likely be warnings (not that we need more) about why new technology should be rolled out incrementally and with care. And look, I could be wrong about Ed. One problem that it maybe solves is helping students and families whose first language is not Spanish or English. Los Angeles is a diverse, multilingual city, so providing a tool that translates school bureaucratese into Tagalog or Persian might genuinely serve a need. If that turns out to be true I will update my views about how useful chatbots as customer service agents could be. Current view: chatbots using generative AI provide slightly better experiences than confusing and increasingly ad-filled web-based search results. They also carry risks too numerous to list in a short essay.

The lessons of Edison

The lessons of Ed extend beyond sympathy for LAUSD technologists and officials trying to figure out how to respond to the perils and promise of generative AI. I hope optimists who uncritically celebrate the latest talking points take note as well. I get that the pressure to say something on a regular basis on a blog or newsletter can lead to being wrong on the internet, and I don’t want to be that guy in the XKCD cartoon, but since the exchange of ideas is the path to truth in a democratic society, I’m going to critically engage

.His post LA Unified School District Electrifies Education with AI in Only 18 Months hit a nerve. I subscribe to Bouschard’s Substack Education Disrupted: Teaching and Learning in An AI World because I find it generally informative if sometimes overly optimistic. His post last Saturday follows a trend of techno-optimists treating history as superficial evidence for whatever point they want to make, as if saying AI is the new printing press makes an obvious case that we should implement generative AI for everything at full speed without considering questions of how and why we implement new technology. Bauschard argues that the history of electrification in London is a model for understanding the distribution of generative AI in education and that Ed is an amazing achievement. As he puts it, “The AI infrastructure — today’s “electricity” — is built and students are connected.” In Bauschard’s view, Ed is evidence that the distribution of the future in the form of generative AI is proceeding smoothly and that while the electrification of London took 40-50 years, Los Angeles accomplished the distribution of AI for education in just 18 months. Amazing!

The analogy with electrification is an excellent context for thinking about what the big announcement about Ed means for education. But the actual history doesn’t teach the lesson Bauschard thinks it does. The first electric power station in England was not the Deptford Power Station in 1889, as Bauschard suggests. The Holborn Viaduct power station, aka the Edison Electric Light Station, opened seven years earlier. It ran on DC power because Thomas Edison and other boosters convinced City of London officials that they had this electricity thing all figured out. The Edison station, which powered street lighting and a handful of private residences, closed four years later, wiping out investor capital, and more important, forcing the City to reinstall gas lines. The reason? Instead of implementing electrification carefully on a small scale and learning from those experiences to guide adoption, they made a splashy, headline-producing investment that blew up in their faces.

Note: this image is from Caroline's Miscellany, a lovely blog containing random bits of history about Deptford, London, and Brittany.

I believe technological innovation is fundamentally good for humanity in the long run, but attention to actual history reveals the complex and messy reality that social change driven by new tools has costs, and produces winners and losers. In this case, the financial winners were George Westinghouse and others using the AC power transformer technology developed by William Stanley. The Deptford Station successfully started London down the path of electrification seven years later than the initial big rollout of the Edison station because it benefited from years of experiments and projects that proved that AC power was the best way to address the specific use case.

Tech journalists and bloggers are deeply invested in telling the latest version of the war of the currents, casting figures like Musk and Altman in the roles of Edison and Westinghouse. If you care about who wins the game of venture capital that makes sense. However, I find greater value in publications like The Markup and blogs like Understand AI and Mathworlds who are interested in the impacts of generative AI on the users of technology. I am being a little bit mean about Bauschard’s post. He actually links to, but apparently didn’t read, a cautionary tale about Sebastian Ziani de Ferranti, “the man of vision” responsible for building the Deptford Station. Deptford implemented an approach to AC power of increasing the electrical loads to a higher voltage than many experts believed safe. Ferranti faced skepticism and a regulatory inquiry that slowed progress.

It turned out that maybe the safety-minded skeptics had a point. An employee error caused a fire in November 1889, leading to a three-month delay, derailing the financing and Ferranti stepped down.

Many customers had deserted the company, and the number of lamps connected to the system had dwindled from 38,000 to 9,000. It's not surprising that the LESCo Directors were worried men, finding it difficult to maintain faith in Ferranti’s bold concept. The company had lost a lot of money. The hopes of achieving large scale supplies of electricity to London seemed to be vanishing before their eyes, while many of the most eminent men in the field were still insisting that the future of electricity lay with much smaller low-tension stations.

Ferranti left the project, but his proposal for high-voltage distribution ended up being the model on which modern electrification proceeded. Even that success story leads to a more complicated account of the Deptford Station than Bauschard suggests.

However even with Ferranti gone, Deptford was back in service by August 1891. The Company’s old customers were returning as fast as they could be reconnected. But by November of that year, the system had collapsed again. They soldiered on for a few more years until in 1900, it was decided to shutdown for 6 months in order to replace both cables and plant. From then on the Deptford Station went from strength to strength, culminating in a further power station being built alongside, called “Deptford West” and being commissioned in 1929. Deptford East as the old station became known was rejuvenated in 1953 when an extension was built to accommodate an HP station, known as Deptford East HP. Generation ceased on site finally in 1983.

The lesson of the Deptford Power station for expectations about widespread and easy adoption of generative AI by school districts is profoundly at odds with Bauschard’s view that the mission is easily or quickly accomplished. I wish the LAUSD luck as they grapple with the disconnect between what Ed actually does and the expectations generated by their overblown talking points echoed by credulous bloggers and journalists.

𝐀𝐈 𝐋𝐨𝐠 offers links, analysis, and reflection on developments in AI and education. Learn more here.

If you liked what you read, consider clicking one of the buttons below. Doing so may convince the algorithm to share with others. Or, you could bypass the algos by sharing the old-fashioned way: email!

𝑨𝑰 𝑳𝒐𝒈 © 2024 by Rob Nelson is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0.