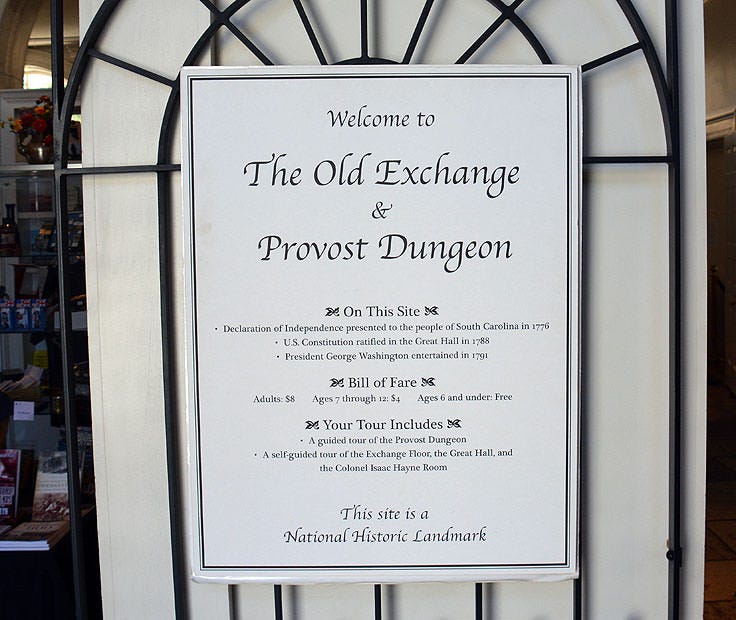

Hello. My name is Rob Nelson. I work in the provost’s office and I’m a bureaucrat. I usually get a laugh when I use that line to introduce myself. The joke works–if it does–because no one willingly identifies themselves as an agent of bureaucracy. Working in the provost’s office subtly extends the joke (at least in my mind) because as tourists visiting Charleston, South Carolina, discover, the title of “provost” has also meant something like sheriff or marshal. So, now that you understand the subtleties: Hello. My name is Rob Nelson. I’m a bureaucrat working in the Provost Dungeon.

At some level, we understand that as we grade, submit requests, process requests, fill out reports, read reports, and do nearly anything transactional within “the system,” we do the work of bureaucracy. If you get a paycheck from a college or university, chances are you are a bureaucrat. But being part of the system is not something that anyone feels proud of. And it does not build community. In fact, the opposite is true. We frequently create community through a sense of shared grievance about bureaucracy. The best way to connect with someone you just met at a university is to trade stories of the catch-22s and petty despotisms of the bureaucratic systems that govern our work as teachers, students, and administrators. Let me tell you this absurd thing the system made me do is a much better opening line than I’m a bureaucrat.

And at some level, we know bureaucracy is necessary. Large, complex organizations run on data and control, which is exactly what bureaucracy provides. The university isn’t complying with some government reporting requirement or regulation? Don’t know how much money you are spending or what your employees are up to? Teachers don’t have time to do administrative tasks? Students up to something bad? The answer to all those questions: Hire a bureaucrat! At the end of the nineteenth century, universities and colleges in the United States started hiring bureaucrats to help manage the modern organizations they were building. Before long the bureaucrats working full-time on administrative tasks outnumbered the part-time bureaucrats who taught and did research.

University bureaucracies continued to grow through a process of accretion, over time and in layers, which means there is no rational design to them. They have become labyrinthine dungeons. Any knowledge one acquires about these structures will be contradictory and obtuse. Attempting to remove elements of the structure will have unintended consequences, sometimes quite dismaying, as many a bureaucrat has discovered. By the way, this description applies just as well to large models built on generative transformer technology and trained using human feedback. Just replace bureaucracy with LLM in the sentences above to see what I mean. Bureaucracies and large models are both forms of artificial intelligence, impersonal and impenetrable in their outputs. Note: I’m far from the first person to point out the similarities between AI and corporate bureaucracies. The first time I recall hearing them analogized was Charlie Stross in Dude, you broke the future.

Generative AI promises to transform our dungeons by relieving bureaucrats of the burdens of mundane administrative effort. Or, maybe by replacing the bureaucrats with autonomous machines? In the worst case, it will relieve bureaucrats of responsibility, including their responsibility to other humans. In the best case, it will enable us to spend less time counting and reporting, and more time talking with the people we work with, especially students. The prospect of an AI transformation of knowledge work has created a great deal of anxiety and excitement among the minority of bureaucrats paying attention. I suspect the number of people noticing these changes will increase this year and many will gravitate to the extremes of despair or enthusiasm. Readers of my essay on techno-pragmatism know that I am looking for ways to approach the prospect of significant change with something other than pessimism or optimism.

The traditional answer to such complaints is “Let’s hire some bureaucrats to deal with this.” And that may happen. But maybe this is our chance to change the bureaucracy rather than add another layer?

My case for pragmatic, positive change in higher education starts with the belief that the adoption of new technology is best managed through incremental, small-scale experiments that have the potential to scale up or become models for larger experiments. I see evidence that most institutions are approaching the adoption of generative AI cautiously and am gratified. Given that the splashiest announcement of the last six months in higher education and AI news is that Arizona State University is “collaborating” with OpenAI to create a few pilot projects, I think it is safe to say that universities are moving with our usual, deliberate speed when it comes to AI.

Of course, that creates its own frustrations, and not just for the companies trying to sell us on the new technology. Among the complaints from within the academy over the past year have been “Why won’t the university administration tell us what to do about AI?” “We don’t have time to figure out AI!” “The students are up to no good with AI!” The traditional answer to such complaints is “Let’s hire some bureaucrats to deal with this.” And that may happen. But maybe this is our chance to change the bureaucracy rather than add another layer?

While I am not convinced that teaching will change any time soon, generative AI is going to transform our work as bureaucrats, starting right now if Ethan Mollick is right. Co-pilots, natural language interfaces, and new forms of machine data analysis are here and are being used by bureaucrats today to accomplish routine knowledge work, often in isolation and with no guidance from bosses (good?) or coordination with other bureaucrats (bad!). That means, as James Brown says, we need to “Get on the Good Foot.” We need to get ready to make our best moves.

Getting on our good foot means that our values, not our fears, should guide how we design experiments with generative AI, experiments that will show us what works and what doesn’t. We don’t typically think about design when we plan change at universities (in fact, we don’t do much planning for change at all), but we need design thinking to plan our next steps. If generative AI is transforming knowledge work the way steam and electricity transformed manual labor, then institutions that create and teach new knowledge need to make James Brown-level moves. And as natural and responsive as James made it seem, his moves were worked out in famously intense rehearsals with his musicians and dancers. Bureaucrats need to start practicing the dance with generative AI—not alone in front of their screens, but in rehearsals that allow us to choreograph our work together with the new tools.

You run across insightful people all the time when you work at a university. I recently discovered George Demiris, a professor based in the nursing school at Penn who incorporates democratic processes into healthcare using design thinking. He summarizes the core principles of participatory design as:

Treating workers as people, rather than performers of defined functions.

Acknowledging that work tasks cannot be understood apart from their context.

Understanding the impact of technology on its users.

Recognizing that how people use a technology defines how effective that technology is.

Those principles show how we should design and implement pilot programs for educational administrators to try out generative AI. Following them may avoid turning our bureaucratic dungeons into bureaucratic dungeons powered by AI. I don’t dare believe that we could create something that will make us proud educational bureaucrats, but I do believe we can make better bureaucracies than the ones we have today.

Bureaucrats should be agents of educational reform

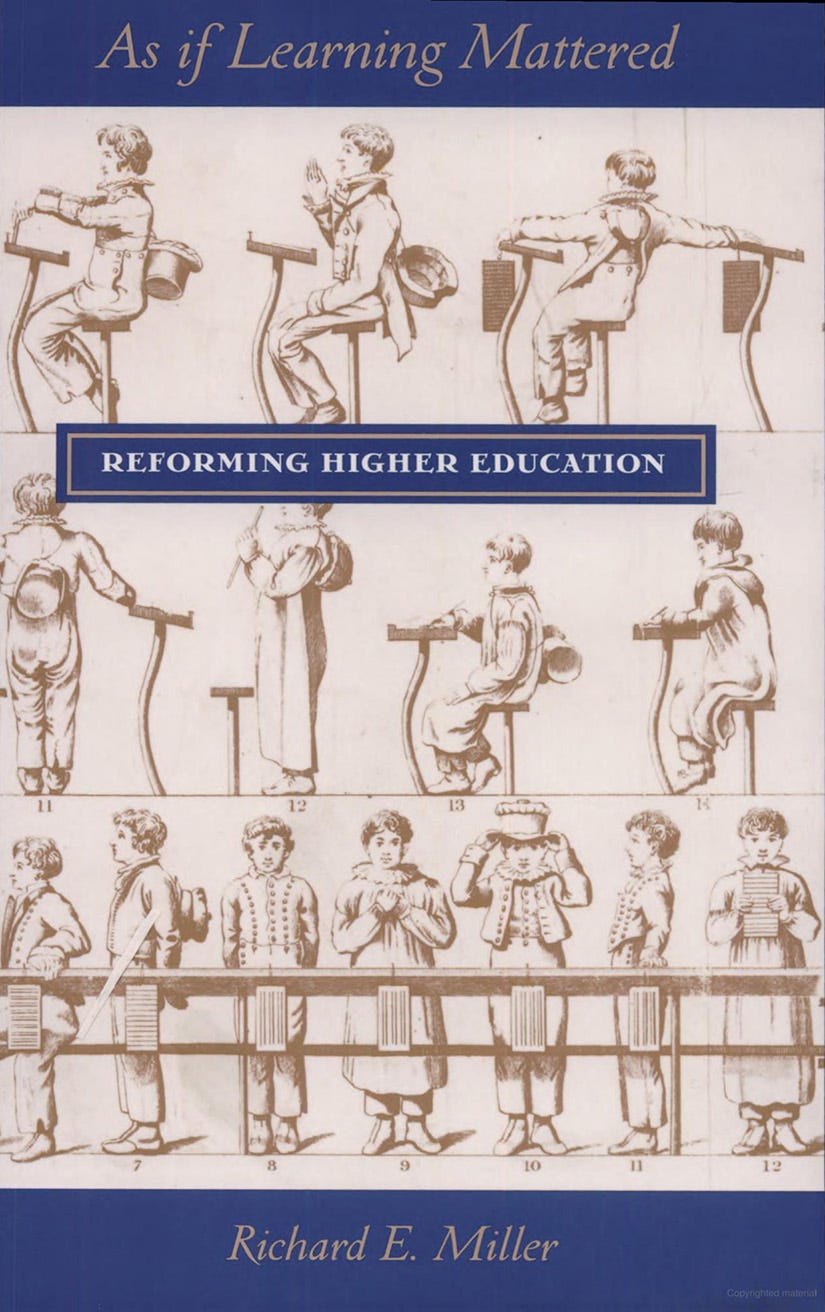

The book that has most shaped my views on how to change educational bureaucracies for the better is As If Learning Mattered: Reforming Higher Education by Richard E. Miller, which among other things, explains why educational institutions have successfully resisted wave after wave of reform efforts and provides much-needed historical context for the current culture wars. You can read the author’s reflection on the 25th anniversary of its publication here.

As If Learning Mattered provides a model—the hybrid persona of the intellectual-bureaucrat—that helped me understand that my work as a teacher and writer is deeply connected to my work as a bureaucrat. It also helped me abandon the hierarchy that values scholarship over teaching and administrative work. It gave me a framework that treats these activities—administration, teaching, and writing—as an improvised dance embedded in an institution that despite its multiple faults accomplishes good things in the world, things like giving people opportunities to learn and to get vaccinated for COVID.

As If Learning Mattered is now available online through the WAC Clearinghouse series Landmark Publications in Writing Studies.

Academic publishing is a labyrinthine dungeon

Librarians and editors are bureaucrats too, and their bureaucracies need remaking as much as the ones that support teaching and learning.

The Scholarly Kitchen blog has long been how I stay up to speed on what’s going on in scholarly publishing. Earlier this week, they published a short version of an article titled The Second Digital Transformation by Roger C. Schonfeld, Oya Y. Rieger, and Tracy Bergstrom of Ithaka S+R.

The longer piece is worth reading as it puts the impact of generative AI and other types of machine communication in the broad context of the multiple challenges facing scholarly publishing. I came away hopeful that librarians, editors, university leaders, and publishing executives could build a better publishing infrastructure.

Here is my favorite of their many recommendations:

We recommend that universities and publishing organizations convene a strategic discussion, informed by user research, to develop new approaches to connecting content with users, both humans and machines.

Libraries are not dungeons

The one place on campus I will never think of as a labyrinthine dungeon is the library stacks. Here is my favorite piece of writing on Substack—something I found just after I created an account on the platform—an essay from

on the history of the open-stack library.Breen’s new book, Tripping on Utopia: Margaret Mead, the Cold War, and the Troubled Birth of Psychedelic Science, is sitting on my nightstand waiting to be read. It got a rave review in the New Yorker last week. You can read about a very strange backlash to his book on his blog,

. The type of backlash probably feels familiar to those who write about politics, but to historians, or at least this historian, it feels quite disturbing.Fridays are for thinking about design thinking

Interested in design thinking in education? Here is a brief overview with links. You might also check out the Laboratory on Design Thinking at University of Kentucky. John Nash is the director there and writes on generative AI topics.

AI Log offers links, analysis, and reflection on developments in AI and education each Friday morning. To receive each weekly log in your email inbox, visit my blog on Substack. To receive a notice each Friday in your LinkedIn feed, click here. All content is free and I never share your email address with anyone.

If you liked what you read, consider clicking one of the buttons below. Doing so may convince the algorithm to share with others. Or, you could bypass the algos by sharing the old-fashioned way: email!

𝑨𝑰 𝑳𝒐𝒈 © 2024 by Rob Nelson is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0.

Great post Rob, thanks for sharing. Added "As If Learning Mattered: Reforming Higher Education" to my list—sounds very relevant.