Grading is a black box inside a very old, very slow AI

AI Log reviews The Unaccountability Machine and Failing our Future

Anybody who has dealt with a corporation or bureaucracy of any size, and who is over the age of forty, is likely to have a vague sense that you used to be able to speak to a person and get things done; the world wasn’t always a maze of options menus. —Dan Davies

Just talking about the mark, the letter, the grade itself does not really do justice to the complexity of the issues at hand. —Josh Eyler

The fact of mass distress

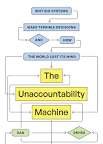

Most of us seek to explain the rise of anti-liberal, anti-elite political movements like MAGA and Brexit by analyzing their political or cultural content. Inevitably, this gets complicated, so much so that we end up arguing over interpretations of social ideas expressed by candidates and why or whether they appeal to voters. In The Unaccountability Machine, Dan Davies argues for simplicity. Let’s treat elections as a decision-making mechanism for any system that “operates by consent of the decided-upon.” Thus reduced, Davies explains the “family resemblance” of successful political movements in the 2010s led by Modi, Beppe Grillo, Farage, Erdoğan, and Trump as “each of them, in their own culturally specific context,” acting as a channel of information.

In this way of thinking, inputs and outputs are what matter most. Decision-making mechanisms matter, too. But if you want to understand a system, you’ll get lost if you dive into those mechanisms and analyze their workings in detail. Too many unanswerable questions. Too much information.

The protagonist of The Unaccountability Machine, Stafford Beer, was the pioneer of using the now ubiquitous term “black box” as a way to demarcate complexity in a system in order to contain it. Once contained, analyzing the system becomes easier because you stop trying to explain what you do not really understand. Here’s Davies:

“This is a matter of respecting the complexity of the problem—a genuinely complex system is one in which you cannot hope to get full or perfect information about the internal structure, and cannot have any acceptable degree of confidence that the bits of information you don’t have can be safely ignored.”

Think of the election last November as a black box. We have inputs in the form of complex human wants and desires expressed in a decision recorded as a vote. And we have outputs in the form of election results. Ignore the complexity of why and how voters choose a candidate. Instead, consider the limited information we receive in the output. Candidates like Trump act “as a communication channel for a population which wanted to convey a single bit of information: the message that translates as, ‘HELP! THE CURRENT STATE OF AFFAIRS IS INTOLERABLE TO ME.’” Of course, there was much more voters were trying to convey, but as the post-election commentary demonstrates, we know very little for sure beyond the vote totals. All attempts to explain the why and how of Trump, all the auguries that help us cope by analyzing what happened before the vote, should be ignored to focus on the signal. As Davies says, we should respond to “the fact of mass distress, not its content.” 1

The Unaccountability Machine is not really about the election or politics. It is about how cybernetics, as represented by Beer, can help us understand systems, and perhaps change them. The book talks quite a bit about schooling, and I found it helpful for thinking about educational problems, especially the ones visible in the public discourse since the arrival of Covid-19 and the homework machine known as ChatGPT. Both events precipitated feelings of mass distress, perhaps not unrelated to those connected to Trump and Brexit.

Josh Eyler’s Failing our Future focuses attention on what is perhaps the most important black box in any system of schooling: grading. Eyler believes our efforts to fix schooling should begin with understanding and changing what happens in that black box. He reminds us that what he calls “traditional grading”—the awarding of grades that are automatically translated into numbers and used to rank or sort students—has a history that is only about a hundred years old. He points to Montessori schools and homeschooling as widespread alternatives. Mostly, he focuses attention on a variety of experiments with and, in some cases, actual implementations of alternative models for grading.

Eyler believes that the existence of those alternatives and the research that clearly shows how harmful traditional grading is to students are reasons for optimism about the prospects of replacing traditional grading. I desperately want him to be right. With my sympathies declared, I now want to explore the prospects of grading reform using a few ideas borrowed from cybernetics to think about systems of schooling.

Grading is a black box

Let’s pull out a black marker and draw a box around the practice of grading. Remember that a cybernetic model is not trying to explain the process inside the box. Coloring in the box with black ink leaves us with the inputs, a collection of artifacts produced by a student, and the outputs, a teacher’s evaluation of that work.

This teacher’s evaluation is typically expressed as a number, such as 83 out of 100, or a letter, such as a grade of B. In nearly all cases, the output can translated numerically, such as the practice of converting letter grades into numbers on a scale, so that B becomes a 3.0 on a 4.0 scale. Averaging these numbers as reported at the end of a grading period results in a grade point average (GPA) that can then be used to rank a student’s overall academic performance. This is a crucial characteristic of the output: a number that can be combined with other numbers to position a student inside the system.

Even if principals, superintendents, provosts, educational bureaucrats, and politicians can be made to care about the harm of current grading practices, they will not care only about that.

The complex human purposes and behaviors embedded in the practice of creating artifacts to be graded and the evaluation process itself can now be ignored. Student work goes in. Grades come out. The extent to which a student gained knowledge, mastered a new skill, or meaningfully engaged with a community of inquiry no longer matters. Modeled cybernetically, grading is simply a decision-making mechanism for turning inputs into specific kinds of outputs.

This is not the model Josh Eyler uses to explain grading. Failing Our Future dives into the human mess of grading practices, starting with the contradiction between grading as an evaluation of student work for the purpose of learning and the assessment of student work for the purpose of sorting. The conflict between giving feedback aimed at helping students learn and evaluating them for institutional purposes is confusing for everyone involved. Failing Our Future diagnoses this confusion as the key problem for schooling in a democratic society. Eyler wants to understand grading in order to fix it. As he says, “it’s all very complicated, and just talking about the mark, the letter, the grade itself does not really do justice to the complexity of the issues at hand.”

Indeed, it does not. Yet, the reason we have not changed grading, despite the overwhelming evidence Eyler presents, is the simple fact that the system needs outputs in the form of numbers so students can be sorted. I want to believe that teachers can be the change we want to see in the world, so I find myself thrilled with the enthusiasm Eyler reports among grade reformers. Yet, as Eyler says, there is no way to gauge how widespread the reform is, nor how likely it is to succeed. He describes reasons for hope and the intractable barrier to reform.

At the beginning of any kind of change-making process, the numbers matter less than the act of moving forward itself. The teachers who are doing this work are participating in nothing short of a revolution, a reinvention of education, and they are shifting the landscape for their students. But they cannot do it alone. To truly overturn the regime of traditional grading, we will need educational institutions themselves to change as well.

This is where the black box comes in. In order to be clear-eyed about what’s possible, we need to model the system. Teachers can care about their own practices to the exclusion of the systemic effects and demands. They only have to get the students in their class (and their more engaged parents) to agree to change. Even if principals, superintendents, provosts, educational bureaucrats, and politicians can be made to care about the harm of current grading practices, they will not care only about that. Bureaucrats, especially those deciding policy and budget, will always care about the effective functioning of the system as they understand it.

A is for Apple; B is for Bureaucrat

Like many parents and teachers, bureaucrats are conservative (small c) in their orientation toward institutional change. When confronted with proposals for genuine reform, even ones they are sympathetic to, they think about who will be upset and the unintended or unforeseen consequences. How many apple carts will tip over, and who cleans up the apples? are questions they must ask. Changing the outputs of the grading process such that students are no longer easily sorted will mean a lot of apples on the floor.

The social inertia that keeps grading practices as they have been since the middle of the twentieth century is best explained by a desire to keep apples in the cart, to keep the system functioning in ways that make sense to students and their parents, who experienced more or less the same system. Mess with the outputs, and the entire system is imperiled. Eyler describes ways that the latest generation is echoing arguments for reform that have been made since the current grading systems were put into place. In Tinkering Toward Utopia, David Tyack and Larry Cuban say that such “continuity in the grammar of instruction has puzzled and frustrated generations of reformers.” The question is, What has to change such that reforming the grammar becomes possible?2

Eyler offers a blueprint for change that is as good as it gets, emphasizing the need for transparency, clear communication with all stakeholders, and putting the why of change before the what of change. I put down the book feeling enthusiastic about the prospect. I will continue to push my own grading practices in the direction of prioritizing the needs of my students instead of those of the system. I see no reason that the alternative models Eyler describes cannot become more widespread.

But recent history gives some reason to be skeptical about the prospects for systemic reform. The response to Covid-19 involved rapid and comprehensive changes to grading practices at the level of institutions and systems. Schools deemphasized numerical grading in favor of pass/fail models. They adapted their schedules and procedures to support overwhelmed students. And then, as Eyler says, having succeeded in implementing dramatic change, they reverted “their pre-pandemic grading schemes.”

The pandemic opened a door and let us step into a world where grading is different. Since 2020, we have been backing up and closing that door.

He sees this temporary change as evidence the apple cart is half full. The pandemic adaptations show that change is possible. I see the return to normal procedures as evidence of inertia. No matter how well-recognized the harms and how widespread the desire for change is, our systems of schooling require we produce specific outputs on a specific timetable. The grammar of instruction was confronted with a profound and intense disruption. The system adapted, temporarily reforming, and then returned to familiar processes.

Inside the black box

I failed two students in the first class I taught. One student simply didn’t do the work. Easy enough to assign an F. The other was a first-generation college student who was not prepared by her previous experience to write according to the standards established by the writing program whose curriculum I was teaching. This despite sixteen weeks of heroic effort on her part, meeting with me weekly for office hours and taking advantage of every available support offered by a University that, by every indication, wanted this and every student to pass the course.

I spent a lot of time talking myself into the idea that an F was in the best interests of the student and the institution. Retaking the course would allow her to reach a minimum standard for the written expression of English in an academic environment. This would put her on a solid path to success in whatever major she selected. That’s what I said when I sent the email explaining that she would receive an F for the course and offering to meet to talk about ways she could prepare to retake the course in the upcoming term. “I hope you find time to think about other things and relax during the winter break,” I added. She did not respond to my email.

Some of my fellow newbie instructors facing similar situations talked about finding a way to work around the system. Maybe we simply don’t assign a grade, work with the students over the spring term, and assign a passing grade at the midterm after they master the material. This was, of course, a fantasy to escape the grim reality of assigning an F. I was a newbie teacher, but I had spent four years as an academic advisor. I explained that even if the writing program would allow it (it would not), such a move could jeopardize a student’s academic progress.

For purposes of financial aid eligibility, accumulating credit on a schedule matters. A mark of “incomplete” or “no grade reported” functions like an F grade. Further, since students need to maintain a full-time schedule, having them continue to work in a class they are not registered for is an overload. It would pressure them in ways that could jeopardize their grades in other classes, creating a chain of events that results in a hole too deep to climb out of at the end of the academic year. The structures built around grading each term are unforgiving, and any advising office can tell you that well-meaning instructors who give incompletes often put their students at risk.3

Teachers can carve out some freedoms inside the black box, but even the most supportive schools produce grades on a schedule. Individual student success and the smooth functioning of the system require it. Institutions with alternative grading models still have to create grooves to convert non-graded evaluations into outputs recognizable to downstream systems. Thus, Montessori schools produce reports designed to reassure traditional middle schools that their students can function at the age-appropriate grade level. Evergreen State College, famous for its qualitative evaluations, provides a rubric to help convert their feedback into numbers for graduate and professional programs that want it.4

Letting a serious crisis go to waste

In the spring of 2020, numbers and standards suddenly became less important. Health and welfare mattered more. We adjusted our practices to give students more time, to put less pressure on them. We let them take classes pass/fail or drop after the deadline. We made the hunger games of standardized admissions testing optional. Along with a terrifying public health emergency, we had a grand experiment in rethinking the system along the lines Eyler and many of us want to see.

Today, the experiment is clearly over. The system is returned to its earlier state. The demand for numerical outputs issued on schedule has reasserted itself. We have reinstated standardized admissions tests despite widespread agreement that reducing academic potential to a number correlated with your household income is a problem. Look, the pundits say, high school GPA and a test score have slightly better predictive value than GPA alone. We have to keep doing it this way. Although there is not much evidence for it, they argue that maybe test scores will help identify a few students whose potential isn’t reflected in their grades.5

Davies tells a specific story about exam grades during the pandemic that demonstrates why the prospects for change were fleeting. Due to Covid-19, the regular annual examinations in the Department of Education in Westminster, England, were canceled. Not an unusual situation that year, as so many institutional or system processes were suspended or changed during the height of the pandemic. In order to facilitate college admissions during the crisis, educational bureaucrats in Westminster decided to replace the single measure of A-level exam scores with an algorithm using assessments given by teachers. In other words, they replaced the output of a standardized exam with the output of an algorithm based on grading practices scrambled by the pandemic. This shortcut seemed, on the surface, to make some sense. Why not replace one number with another? The actual result was chaos.

Some lessons were clear. Educational bureaucrats sometimes act idiotically under pressure. Spinning up half-assed algorithms on the fly to replace long-standing procedures is a bad approach to managing a crisis. Other lessons can be gleaned if you see the students chanting “fuck the algorithm” in Westminster as more dramatic versions of students in the US asking, “Without traditional grades and test scores, how will I get into my top choice for college?” Screwing up the outputs and screwing with the outputs are a difference in degree. Distress is the social effect, visible in the Westminster demonstrations and anxious discussions with guidance counselors and admissions officers throughout the US.

The teacher side of this experiment is not all that different. When faculty committees ask, “Without traditional grades and test scores, how can I tell if a student has the skills and knowledge to declare a major or be admitted to a PhD program?” or “How can we encourage academic excellence if we stick with a pass/fail grading model?” they express the fear that changing the outputs will disturb elements of the system they value. The pandemic opened a door and let us step into a world where grading is different. Since 2020, we have been backing up and closing that door.

Universities are very slow, very old AIs

Charlie Stross introduced me to the idea that corporations, really any bureaucratic organization large enough, can be analogized to an artificial intelligence. My favorite examples of him playing around with this idea are here and here. The foundation for Stross’s darkly comic idea is that corporations are “clearly artificial, but legally they're people. They have goals, and operate in pursuit of these goals. And they have a natural life cycle.” He mentions that the life span of corporations in the S&P 500 has been steadily shrinking since the 1950s and is now down to roughly 20 years. Colleges and universities, despite a recent uptick in mortality, tend to be longer lived.

To make it clear that all categories of corporations are AIs, not just for-profits and those like OpenAI attempting to transition, it helps to quote from Dartmouth College v. Woodward (1819), well known to US historians of business, education, and law. Chief Justice John Marshall wrote: "A corporation is an artificial being, invisible, intangible, and existing only in contemplation of the law." He went on to call such an entity “a mere creature of law,” which, from his point of view, was true. For the rest of us, these creatures are involved in nearly all aspects of society, sometimes as benevolent providers of material goods, services, and learning experiences. Sometimes, they appear as monsters, destroying individual aspirations and actively fighting the social good by rigging the system for elites.

We want to see these entities as controlled, or at least controllable, by humans, but thinking of them as AIs helps us understand how they are the ones in control. They have a legal and social existence all their own, and they are as dedicated to their own survival as any human. But they are not human. They are artificial creatures made of rule-governed processes. As Davies puts it, “If a corporation has a set of rules that take inputs and produce outputs in a systematic way, then that’s an algorithm. And the company could be seen as the system that implements that algorithm, in just the same way that a computer runs an artificial intelligence program.”

I learned from The Unaccountability Machine that Stross was not the first person to formulate this analogy. Here is a 2012 paper by computer scientist Ben Kuipers. Kuipers doesn’t have as much fun as Stross does with the idea, but I give him full credit for articulating what I take to be the essential conclusion to be drawn from the fact that corporations have their own lives and goals: “To co-exist well, we need to find ways to define the rights and responsibilities of both individual humans and corporate entities, and to find ways to ensure that corporate entities behave as responsible members of society.”

The social problems that result from irresponsible AIs are made harder to fix by the tendency to blame other humans for their intractability. We complain about the deans and provosts who won’t take corrective action. Blame students who don’t care enough about their own education to put in the work. See the problem as colleagues who sell out/phone it in/ignore our ideas. These complaints may be valid, but the behavior of the offenders can often be explained as responses or adaptations to the algorithm. The algorithm may have been built by humans and may be mostly constituted by human decisions, but the structure running it is empowered by law and social convention to make its way through the world on its own terms. As functionaries of the organization, each of us is obliged to perform our duties in such a way as not to damage the structure or the smooth functioning of the algorithm.

The truth is we are all little black boxes turning inputs into outputs, working inside an entity with logic and rules that seemingly cannot be changed from the inside. From the president to the lowest-paid adjunct or the principal to the newest teacher, we each have some small freedom to do what we will with the inputs we have to work with as long as the outputs necessary to keep the entity functioning are provided on schedule. The result of all this is that the only thing worse than a functional AI is a dysfunctional AI.

Designing freedom in the time of monsters

Things appear bleak. If you are a teacher, the educational institution that pays your salary is an AI monster. Our system of schooling is a collective of these monsters, eating and shitting numbers, while humans function as gut bacteria turning the human experience of learning into inputs and outputs governed by the logic of AIs we created but lost control over. It feels like we live in a world of stable, functional entities living their best artificial lives while making us miserable despite a small degree of freedom in our little black boxes.

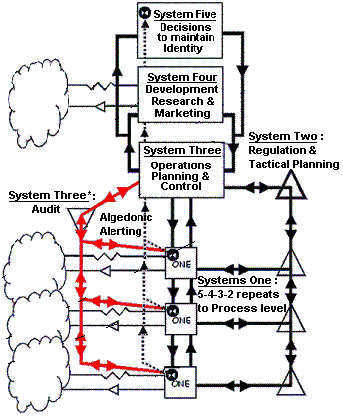

In Designing Freedom, delivered as the Massey Lectures in 1973, Stafford Beer argues repeatedly that these entities, these “large and powerful pieces of social machinery which suddenly seem not so much protective as actually threatening,” are not stable. Instead, they are dynamic viable systems. They are always adapting to their environment. Understood this way, Josh Eyler is right about the potential for institutional change.

The algorithms may be too complex for any one human to understand or manage, but their behavior can be changed by humans. After all, they are made up of human decisions. The pandemic required drastic adaptations to sudden changes in the environment. We did it. We. Humans. Did. It. We changed the algorithms to meet the changing circumstances. We taught online to keep our students and ourselves safe. We changed grading for similar good reasons. And then, uncomfortable with what we wrought, we changed it all back.

The institutions morphed back into something like their earlier selves and again demanded the traditional outputs. We went back to our boxes and our bits of freedom. To maintaing the adaptations would have been uncomfortable for humans and potentially deadly for the AI creatures.

The survival instinct of our institutional AIs is strong. As Beer says, they are homeostatic.

All homeostatic systems hold a critical output at a steady level. But some of them have a very special extra feature. It is that the output they hold steady is their own organization. Hence every response that they make, every adaptation that they embody in themselves, and every evolutionary manoeuvre that they spawn, is directed to survival. So this special trick rather well defines the nature of life itself. It also rather well explains why we cannot change our institutions very easily. Their systemic organization is directed, not primarily to our welfare, but to their own survival.

I said earlier the only thing worse than a functional AI is a dysfunctional AI. I would argue that is not true when the functioning AI is harming humans. Then, it is time for a change, even at the risk of institutional dysfunction and human discomfort.

Our interests as reformers are not the same as those of homeostatic AI systems. They are mobilizing now to respond to whatever chaos is introduced by the Trump administration and to the demographic reality that there will be fewer students enrolling in higher education in the coming decades. There is also the likelihood that fewer will choose to study the humanities and social sciences. Facing this reality, the institutions will look first to survive. We reformers will too, and as uncomfortable as this is to contemplate, it may well be a case of us or them.

Reading Failing Our Future, I wonder if this is already the case. Those of us who believe that the numerical outputs our AIs demand are harmful to our students and who wish to protect the liberal arts have had a tough four years. The next four looks to be even tougher. The institutions that pay us seem on the verge of becoming more monstrous as they adapt to survive. They may not make it. And that’s okay. It is more important that we survive.

Elite colleges and universities have had a long, good life. They brought useful knowledge into the world when they behaved and no small amount of pain when they misbehaved. For nearly four hundred years (much longer outside North America), they have been imperfect expressions of ideals and unrealized promises. Over the course of their lives, we have given them attention, perhaps more than was warranted. Today, they don’t seem to be functioning all that well and seem increasingly dangerous. Given how they behaved last spring, I’m worried that the next time they encounter students engaging in civil disobedience, they may kill someone.

There are non-elite institutions, thousands scattered across the US. Think of all the community colleges, denominational colleges, HBCUs, non-selective state universities, and tribal colleges that barely get attention from journalists, policy researchers, and ambitious students. Heck, think about how few people even know about Western Governors University. Maybe it is time to attend to non-elite institutions rather than continuing to care for the very old, very slow universities whose purpose is to reproduce existing elites.

The Time of Monsters

Gramsci’s quote about the old world dying as the new world struggles to be born is suddenly everywhere. It is, indeed, the time of monsters, and thinking of institutions as algorithmic monsters that need to be tamed helps in two ways. First, it points us to the hard work of changing the culture of an institution. Instead of blaming our human colleagues, it is time to make common cause. Timothy Burke has relevant thoughts. Second, it helps us see LLMs as a potential management technology instead of a homework machine or teaching tool.

This is what I take from Henry Farrell’s post suggesting that “LLMs provide big organizations with a brand new toolkit for organizing and manipulating information.” We seldom think about LLMs in those terms. They are being sold as tools for individuals, as another bicycle for the individual mind. Think instead of using an LLM as the interface to your institution’s policy manual, a way of organizing and mobilizing the collective intelligence of a corporation. That may call to mind automated monsters more terrible than the ones we have, but maybe it is worth considering that it takes an algorithm to manage an algorithm.

As the scope and intensity of change increases in response to the fact of mass distress we saw in November’s election results, reformers should stay focused on what we want the educational system outputs to be. Fans of cybernetics are fond of Beer’s axiom, “The purpose of a system is what it does.” If we want schools to stop sorting students in harmful ways and, instead, support learning and growth, we must attempt to create organizational outputs that achieve that purpose. Abandon institutions incapable of changing their outputs. Repurpose and reform institutions so they do the work of democracy. The purpose of a system is what it does.

The Unaccountability Machine is available in hardcover from Profile Books. A paperback edition comes out from The University of Chicago Press in April.

Failing our Future is available in hardcover from The Johns Hopkins Press.

I first encountered Stafford Beer during a brief but intense interest in management theory. After dipping into some of his greatest hits, I placed him in a bucket along with Peter Drucker as worth coming back to someday. Kevin Munger reintroduced me to Beer in this essay. Henry Farrell convinced me I needed to read him and Dan Davies in this essay.

Larry Cuban has an excellent series of blog posts from 2019 about efforts to challenge the “Grammar of Instruction.”

Anyone who teaches gatekeeping courses must confront something like what I discovered as a new instructor and what Eyler’s review of relevant research shows: “the archaic grading systems that were put in place over a hundred years ago” are particularly harmful to capable students who start college less prepared than their classmates.

There is a reason why teaching introductory writing or STEM courses is mostly left to graduate students and underpaid adjuncts. It is hard, thankless work. After two years teaching introductory writing, I escaped to teach cultural studies and history, where grading was less standardized and I had greater freedom.

Two references worth calling out. The first is the 1998 book titled Inside the Black Box by Paul Black and Dylan Wiliam, which argues for formative assessment. Here is a brief overview and appreciation.

The second is Henry Louis Gates’s most recent book, titled The Black Box. It would take another 5000 words even to begin exploring the resonances between Stafford Beer’s use of the term and the way Gates uses it to mean “the figurative black box in which people of African descent were, and continue to be, confined,” so I’ll simply say that I think this may be worth doing, but not today.

I’m relegating this rant to a footnote because it is about test scores, not grading.

Early in 2024 there was a lot of chatter about standardized admissions tests. David Leonhardt and other pundits cheered elite colleges as they ended their pandemic experiments with making SAT and ACT scores optional. These pundits talked a lot about a single academic study that looked at test scores and grades of high-achieving students who were admitted or waitlisted at a handful of elite colleges during the pandemic. They also talked about this committee report, issued during the pandemic, from the UC system faculty senate that analyzed test scores from 2010-2012.

Decades of previous research show that high school grades weakly predict future grades and that including standardized test scores slightly improves the predictive power of models that try to do this. It is possible that one study and one committee report about high-achieving students at highly selective institutions during the pandemic is a harbinger of a change in the predictive power of standardized test scores for all students. Even if you’re enthusiastic about the prospect of standardized tests because you believe, based on limited evidence, that they help identify talented students who would not otherwise be admitted to highly selective colleges or believe, based on limited evidence, in grade inflation, please evaluate these two studies in the context of a larger body of evidence that suggests that the least bad predictor of college grades is high school grades.

Kudos, Rob, for such an informative review, and this perspective on institutions, inertia, and a possible path forward. The annotated reference list is a gem.