Banal impersonations and historical reenactment on the cheap

Do LLMs based on historical figures offer anything of educational value?

John Warner calls historical chatbots “digital necromancy.” Mike Kentz proposes we “grade the chats.” I think LLMs are too boring to be educationally useful, but if I squint, maybe I see some value as problems to be solved within simulations and games.

This is the third and final essay in a series arguing against anthropomorphizing LLMs in education. See also my review of Ethan Mollick’s Co-Intelligence and my polemic against pretending LLMs have a mind.

Listening to Nilay Patel’s interview with Replika CEO Eugenia Kuyda I realized that having a chatbot friend is a cultural practice that I am just not ever going to get. Hearing someone explain human-AI relationships is like hearing about Juggalos or modern-day homesteaders. These are not choices I would make, so they are hard for me to understand. But neither are they choices that directly harm others. I have a high bar for condemning other people’s cultural practices. After all, reading novels, as I do nearly every evening, was once considered a moral poison.

Living and letting live does not extend to what we should do in the classroom. There, I share John Warner’s intolerance of historical chatbots and agree with his reasons they should be rejected. As he points out, chatbots make for great demos. A favorite character come to life! A chat with a dead president! For a couple of minutes, talking with an LLM dressed up in a word costume from the past seems fun. But then what? The longer I chat with a simulated cultural figure the more I want to pick up a book.

In special issue 2.1 of Critical AI, Maurice Wallace and Matthew Peeler argue this is because LLMs interrupt the skepticism fundamental to historical thinking and cultural analysis. Students learn to ask “why?” as they learn to read.

On some level, automated programs like Khanmigo threaten this constructive skepticism. By pretending historical authenticity, they endow their impersonations with an air of direct authority no skepticism can easily challenge.

In their view, such “banal impersonation” not only serves as armor against skeptical inquiry, it also whitewashes history of its authentic voices. They focus on the unfortunate reporting about Khanmigo’s Harriet Tubman chatbot in the Washington Post last year, writing that the LLM’s voice does not suggest “any relation to the insurgent, gun-toting fugitive and Union spy named Tubman.” They point out the impossibility of recovering “the spoken fidelity to country, district, and gender that purports to humanize speech—to say nothing of the peculiar calculus of social intonation, regional variations in pace of speech, vernacular vocabularies, and functional speech disorders” of a specific individual.

Given the challenges LLMs have with racial bias, we should be thankful application developers stick with banal impersonation rather than creative reconstruction of voice. LLMs are simply not capable of doing the cultural work of presenting dialects or phrasing of Black or Asian historical figures. So, guardrails go up to make sure nothing weird or unpleasant happens.

LLMs generate language that has emotional and moral impact, but unlike writers or re-enactors, an LLM has no agency or ethical understanding. Educators ask students to engage in a discussion with an LLM, thinking that this is similar to historical reenactment, a sort of virtual Colonial Williamsburg on the cheap. This misunderstands the context and the educational potential of LLMs.

Historial reenactors working in public history are performers who understand what it is like to be curious students. They also know a thing or two about dealing with disengaged students who act out on a field trip. They teach through a form of serious play, where both sides of the interaction understand the experience as a simulation. LLMs do not have an understanding of context, which seriously limits their educational value. With no awareness of the difference between the colonial past being performed and the present-day audience interpreting the performance, they are unable to follow the shifts in context that happen when students ask questions from different angles.

Natural language interactions invite the perception that LLMs are Socratic, that through dialogue they create learning, but such simulations are lousy substitutes for directly engaging human minds. Just because an LLM can generate language doesn’t mean it can teach.

Are books better than LLMs?

You could argue that this is true of reading. A book has no mind and no awareness of social context. The written word is even more limited than an LLM. At least a chatbot can respond to a question. Maybe my concern about generative AI in this context is just my discomfort with a new form of culture. If so, I’m in good company.

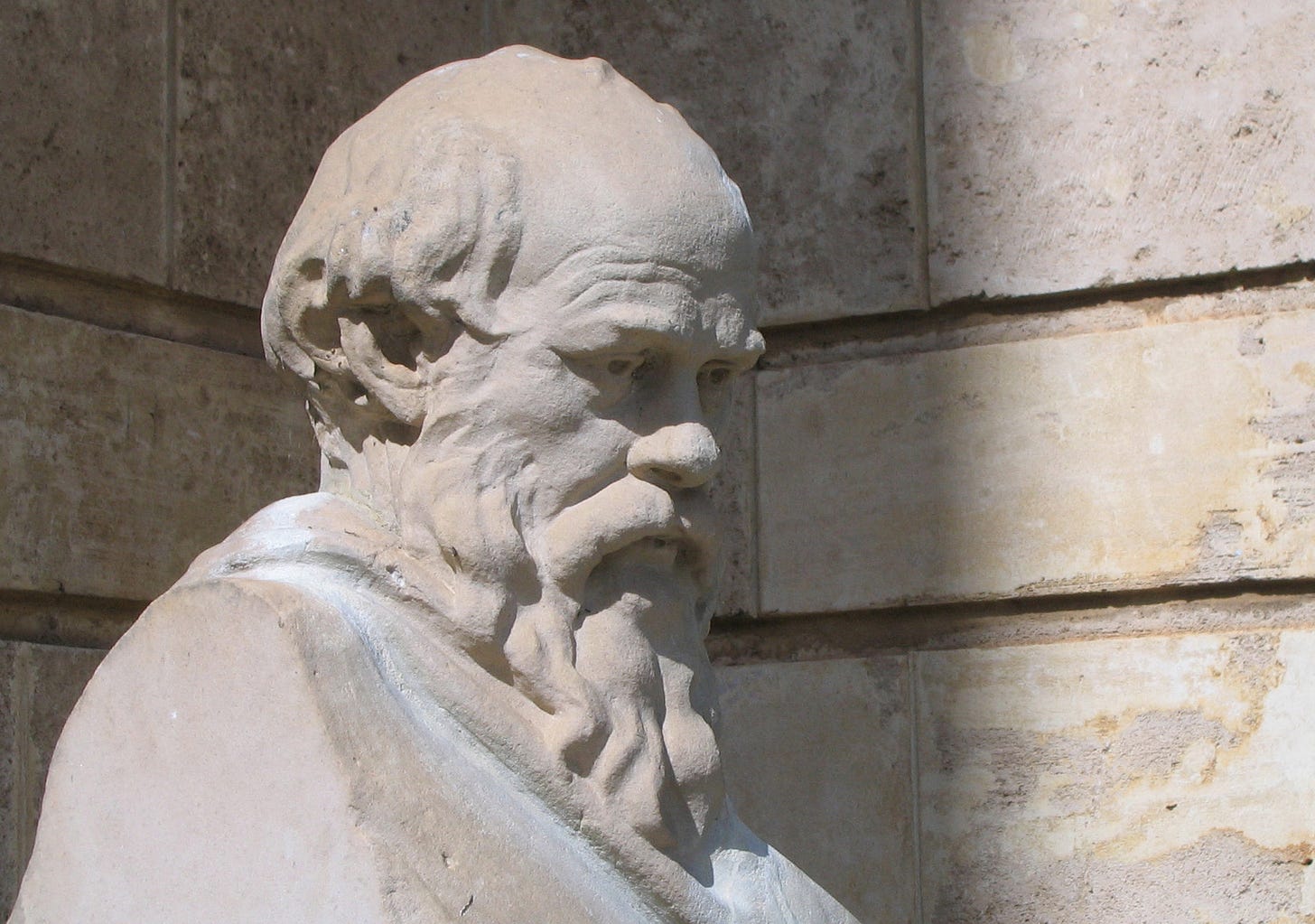

Socrates was skeptical about the value of writing; at least, that’s how Plato presented his position in Phaedrus. Socrates tells the story of Theuth, an Egyptian scholar reported to have invented writing. Thamus, the Egyptian god-king who must decide how the invention will be used, explains why the technology is not an aid to memory, as Theuth believes, but its opposite. Reading words “will create forgetfulness in the learners' souls, because they will not use their memories; they will trust to the external written characters and not remember of themselves.”

Later, Socrates damns the written word in much the same terms I am damning LLMs. Books have no awareness of context or moral agency.

I cannot help feeling, Phaedrus, that writing is unfortunately like painting; for the creations of the painter have the attitude of life, and yet if you ask them a question they preserve a solemn silence. And the same may be said of speeches. You would imagine that they had intelligence, but if you want to know anything and put a question to one of them, the speaker always gives one unvarying answer. And when they have been once written down they are tumbled about anywhere among those who may or may not understand them, and know not to whom they should reply, to whom not: and, if they are maltreated or abused, they have no parent to protect them; and they cannot protect or defend themselves.

We should keep in mind the irony that this speech against the value of the written word is presented in the written form of a dialogue, a dramatic reenactment of intellectual engagement between two humans. It was produced by a mind and written by the hand of an early and influential practitioner of writing as thinking. To read Plato is not to converse with him but to be presented with a cultural artifact designed to invite skeptical inquiry.

And don’t LLMs offer the same? The moral panic about chatbots may be as misplaced as the panic about Wikipedia a decade ago. I have described LLMs as transformer-based culture generators because they generate artifacts, including written text, indistinguishable from those produced by humans. They produce an averaged-out, banal artifact constructed from the vast oceans of internet data. Their outputs join an already existing catalog of banal artifacts written and edited by humans.

That’s my problem with chatting with an LLM to learn history. They’re boring and unhelpful compared to great writing. When I tried speaking with Socrates, I found it remarkably similar to speaking with Eliza. The Socrates bot simply turned what I wrote into rather unimaginative questions. It was able to answer some of my questions with encyclopedia-like generalities, though without encyclopedia-level reliability. Seen in this light, perhaps, as Mike Kentz argues, talking with one can become a form of critical inquiry, an attempt to overcome the banality of so much human discourse. The value of an LLM is that it manifests mediocrity so that students measure their own thoughts against it. Grading the chat becomes an exercise in plumbing the shallows of an LLM’s cultural understanding.

Perhaps there is value in the dialogic process of using natural language to query a database drawn from a writer’s corpus. I decided to try out a specific use case. I pretended I was an undergraduate whose teacher suggested spending fifteen minutes talking with a historical chatbot about potential paper topics. I went to Martin Puchner’s custom GPT for W. E. B. Du Bois. I was grateful to find that it didn’t attempt to adopt his style or diction. I was less happy with its answers.

Channeling my inner undergraduate looking for a topic that might involve screens instead of pages, I asked about Du Bois’s views on television. It returned a general overview of his views on race and criticisms of the news media. Here is how it concluded the answer:

If Du Bois had lived longer to see the full impact of television, it is likely he would have critiqued its role in either perpetuating racial stereotypes or potentially serving as a tool for education and social change. His views would have probably emphasized the need for more balanced and accurate representations of African Americans and the importance of media literacy in combating the negative effects of biased portrayals.

That answer gives the impression that Du Bois never wrote anything about television. Yet, his 1953 essay “The Social Significance of Television” would make a great starting place for an undergraduate research paper on Du Bois and mass media. But, the LLM was unable to suggest readings beyond Du Bois’s best-known work. And when I tried to explore concepts or ideas, it stuck to the most obvious. No matter how specific my questions, the answers were always about “the color line” and “double consciousness.”

I can see my sharpest students finding ways to turn an LLM’s banality and tendency to overgeneralize into something interesting, but they are perfectly capable of developing strong project ideas on their own. What I need is a way to help students who find it difficult to move past the general and catch hold of a topic that speaks to their interests. I see no evidence that historical chatbots can do that effectively. That’s not a surprise. After all, my own one-on-one interactions with a student struggling with an assignment don’t always help. But at least I know when I fail, and I can direct students to others who can help.

Looking for the educational value of transformer-based language models

It is tempting to blame Sal Khan and the ed-tech entrepreneurs offering personalized AI tutors for our problems. But, the tech barons are simply offering solutions aligned with the bureaucratic systems of schooling that emerged over the past two hundred years. We have built systems focused on individual achievement based on measurable outcomes. Schools gather students together for several hours a week and teach them that thinking consists of preparing to take tests and that good scores are the whole point. Schools teach that good writing fits the formula of a five-paragraph essay and always starts with a clear thesis. No wonder many students, when given the opportunity, use ChatGPT or ask someone else to do the work. John Warner nailed the situation days after ChatGPT’s release.

What teachers and schools ask students to do is not great, but that asking is bound up with the systems in which it happens, where teachers have too many students, or where grades or the score on an AP test are more important than actually learning stuff. It’s not just that we need to change how and what we teach. We have to fundamentally alter the spaces in which this teaching happens.

Maybe by shining a light on the systems that produce boredom and passivity, LLMs will jolt us into more creative approaches to teaching about culture. Staging a scene from Romeo & Juliet is a better strategy for student engagement than having students chat with a Shakespeare bot. Asking students to explain the Gettysburg Address will have more educational impact than asking them to discuss the Civil War with an LLM attempting to simulate Lincoln’s beautiful, nineteenth-century language.

This is not a new or radical idea. Susan Blum, Alfie Kohn, and many others have been urging the nineteenth-century idea, born of the kindergarten movement and John Dewey’s experience with the teachers at the University of Chicago Laboratory School, that education in a democracy must be social, that school is not preparation for life but is itself an important form of democratic social life. There are teachers and schools all over the world that bring those ideas and practices to the classroom. Maybe generative AI can be of use to the ongoing movement to disentangle learning from the apparatus of the one best system.

Like the wax tablet, the printing press, or the movie camera, the transformer-based language model is just another cultural tool. Figuring out how to use it well is a chance to reflect on our cultural practices.

The potential I see for generative AI starts with cooperative educational games, where LLMs will make non-player characters (NPCs) more lively and interesting. Creating social experiences through simulations that teach cultural history seems a more promising investment than developing better surveillance tools to make sure students don’t use an LLM for homework. Embedding natural language interactions with transformer-based models inside a virtual learning environment isn’t some wild-eyed, hypothetical. As Ben Breem notes in an essay on

, the technology to create these environments exists now. He offers concepts and sketches of the idea.Breem is already thinking past LLMs’ potential as NPCs and finds “the new possibilities opened up on the assessment side to be even more interesting.” Creating an assessment for a team of students who are completing an immersive educational experience in which LLMs play supporting roles is intriguing. And not only for history. Neal Stephensen offers an ambitious vision for a prototype virtual world created out of Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice. What if instead of watching the latest movie adaptation, an English literature class spent an afternoon exploring that environment, discussing the experience, and writing a guide introducing it.

Embedding LLMs in a digital simulation that unfolds in time and encourages cooperation among human players has far more educational value than a chat. Brief interactions, contextualized by a human-created simulation, turn the limitations of an LLM into an advantage. Instead of trying and failing to meet the benchmark of a human teacher, the LLM simply plays a scene as a character. The goals need only be understood by the humans playing the game. Like the buildings in Colonial Williamsburg or the costumes worn by reenactors, LLMs become part of a human-built environment meant to spark imagination and critical thinking. Like the wax tablet, the printing press, or the movie camera, the transformer-based language model is just another cultural tool. Figuring out how to use it well is a chance to create new cultural practices. Perhaps those practices will yield new and better ways to teach the past.

I’ll be updating my own teaching practice this fall by having an LLM augment an online discussion board in my history of higher education class. My hypothesis is that narrowly tailored responses by an LLM may encourage students to write more in their discussion posts, which will give their classmates more to respond to. Stronger posts and responses may enliven online discussions meant to help students prepare for class. If the students are into the idea, I’ll share how this experiment goes in a future essay.

𝑨𝑰 𝑳𝒐𝒈 © 2024 by Rob Nelson is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0.

I really don’t have anything thoughtful to add.

I read this a few days ago and can’t stop thinking about it. (Not only because I have a Phaedrus-inspired tattoo.) i think there is so much room to broaden our traditional canon of literature that is often taught in classrooms as just the bare minimum to start engaging with a wider array of readers.

Adding discursive features, as enrichment and not replacement, has so much cool potential. Anyway, you’re brilliant. Thank you for giving me something to ponder.

LLMs are tools not people!

I like your use case for discussion boards. Narrowing the purpose and scope is key to making currently technologies work well. Just telling it to take on a role is very limited.

I do think it might be possible to build a "historical" LLM that is more useful, but it would take a lot of work curating and structuring the data used by a customized model ... more work than almost anyone would would want to do ... particularly for this purpose.