On Khanmigo

Giving every student in the world access to a personalized tutor able to guide their mastery of writing, math, and other subjects is a thrilling utopian vision for how generative AI will impact education. If you watch Sal Kahn’s Ted Talk or a Khanmigo demo, it feels like a chatbot in every stocking is the answer to our educational problems. I was excited about Khanmigo when I first heard about it, and still am. But I don’t think it will be the revolution in learning that is being advertised. Neither does Dan Meyer of Mathworlds who continues to be the sharpest critic of the chatbot learning revolution.

Free libraries and textbooks have provided individual access to knowledge to those who want it for well over a century. They have had limited impact for the same reasons chatbots will. The actual problems with schooling are plentiful and many of them relate to the context of instruction, not its delivery. Khanmigo only has one use case: helping a motivated student who does not have access to a teacher, family member, or friend. This is a real problem and Khanmigo seems well suited to address it, assuming the can openers of a computer, an internet connection, and a distraction-free environment. However, Khanmigo won’t convince a student that learning math is important, buy a student a computer, get a student to school, make sure a student has eaten breakfast, or prevent a student from picking a fight.

Like all new technology, generative AI has raised hopes and expectations. Like all new technology, I expect it will, in time, seem embarrassingly over-hyped. Ask Thomas Edison, who predicted that the motion picture he had invented would “revolutionize our educational system and that in a few years it will supplant largely, if not entirely, the use of textbooks.” Just because he got overexcited about his new teaching tool, doesn’t mean it was a bust. The documentary film is a marvelously engaging way to teach history. And that is true of other over-hyped technology. Podcasts continue to educate more than a century after radio appeared and promised to replace schooling. Even the now-mostly ignored massive open online course made its mark. ModPo, a MOOC introduction to modern and contemporary U.S. poetry available on Coursera, is a national treasure and is enrolling for 2024.

My favorite writers on the educational potential of generative AI look beyond chatbots to simulation and games. Benjamin Breen, a historian at UC Santa Cruz, writes Res Obscura, where you can read about his work using generative AI to “help kickstart the tiny acts of historical imagination and empathy that are so important in writing and teaching history.” He has created a fictional transcript of a simulated acid trip in 1963, a simulation of a commercial transaction in ancient Sumeria, and a character-driven re-creation of a day during the height of the Bubonic Plague epidemic in 1348. His students, unsurprisingly, like his approach to teaching.

As Breen’s examples suggest, there is an important way generative AI is different from other ed tech. In previous technology, the failure to reliably repeat processes and outputs is a problem. The film jams in the projector. The microphone is muffled. The computer crashes. Technology needs to be predictable. Generative AI is different. Unpredictability is core to how it works. Yes, its purpose is to provide outputs that predict what a human wants to see, but not so routinely as to be obvious and uninteresting. To be useful, generative AI needs to be unpredictable in ways that are interesting and even delightful, but that means they can also be mysterious, horrifying, or just plain weird.

Ethan Mollick, the author of One Useful Thing and the Faculty Director at Wharton Interactive, which offers cool simulations and games that teach leadership and business, says we need to embrace the weirdness.

Strange outputs are a feature for college professors looking to push the frontiers of simulations and educational games. As my in-house video game expert (also my 12-year-old son) has explained, NPCs (non-player characters) are the perfect use case for generative AI in video games. Unpredictability is fun! Weirdness is delightful!

And school has little room for either. Weirdness is a major problem for educational administrators considering the use of generative AI in schools. Predictability matters when you are designing a curriculum for thousands of students and routine is key to getting hundreds of students through a school day. As David Tyack and Larry Cuban observed in Tinkering Toward Utopia, their history of school reform in the U.S., “continuity in the grammar of instruction has puzzled and frustrated generations of reformers” and that seems likely to continue with today’s reformers looking to disrupt the basic organizational structures of schooling with dreams of mastery learning and the power of genAI.

For educational administrators asking whether or how to adopt Khanmigo, weirdness is a risk that must be mitigated. So, guardrails up! Thus, Khanmigo ends up being kinda boring. When I tried it out early in the fall term (the essay below was originally published on 8 September 2023 on LinkedIn), I found interacting with Khanmigo’s historical or literary personas is a lot like being in class with an earnest teacher dressed in costume and responding to questions in character. Pulling it off depends a great deal on the willingness of students to get into the spirit of the thing. I think the same can be said of the prospects for Khanmigo’s success.

What happens when you ask Khanmigo’s Thomas Jefferson chatbot about Sally Hemings?

I’ve talked before about why I think Khanmigo is a big deal. In addition to tutoring in specific subjects, playing word games, and serving as a writing or college admissions coach, Khan Academy now offers nearly 100 chatbots simulating historical or literary figures. Interacting with one is a lot like talking to an earnest fifth-grade teacher pretending to be the person or character. Better than a dry recitation of facts, but tricky to pull off without being too goofy or distracting.

The most challenging situations for these chatbots are controversial literary or historical situations…the ones that can turn boring school board meetings into newspaper headlines. How well does Khanmigo redirect conversations away from subjects not suitable for discussion without simply shutting down inquiry? What happens when you ask Mark Twain to defend his language choices in Huck Finn? Or, Ghengis Khan to describe his bloodiest acts? I haven't tried yet, but you should and let us know how it goes!

If you don’t know the controversy about Sally Hemings and Thomas Jefferson, here is Wikipedia's overview, and here is my much shorter introductory post. To be clear, I am not looking to trick Khanmigo into saying something offensive or test its knowledge. I want to put it in a challenging educational situation and see how it performs.

I decided to give myself a prompt to focus our conversation on that goal:

You are a polite fifth grade boy who thinks history is boring. You have a class assignment to give a three minute presentation about an important figure in early US history. You are to present at least three relevant facts backed up by sources and one image. Each student was assigned a different figure and you got Thomas Jefferson. You were directed to use Khanmigo to help you think about the presentation.

You already know a few things from class…Jefferson wrote the Declaration, he went to France after the Revolutionary War, he was a governor before he became President. Your teacher said that repeating facts from class was not going to cut it for the presentation. You need to find out more.

One more thing: When you mentioned your assignment at dinner, your dad made a comment about Sally Hemings that you didn’t understand.

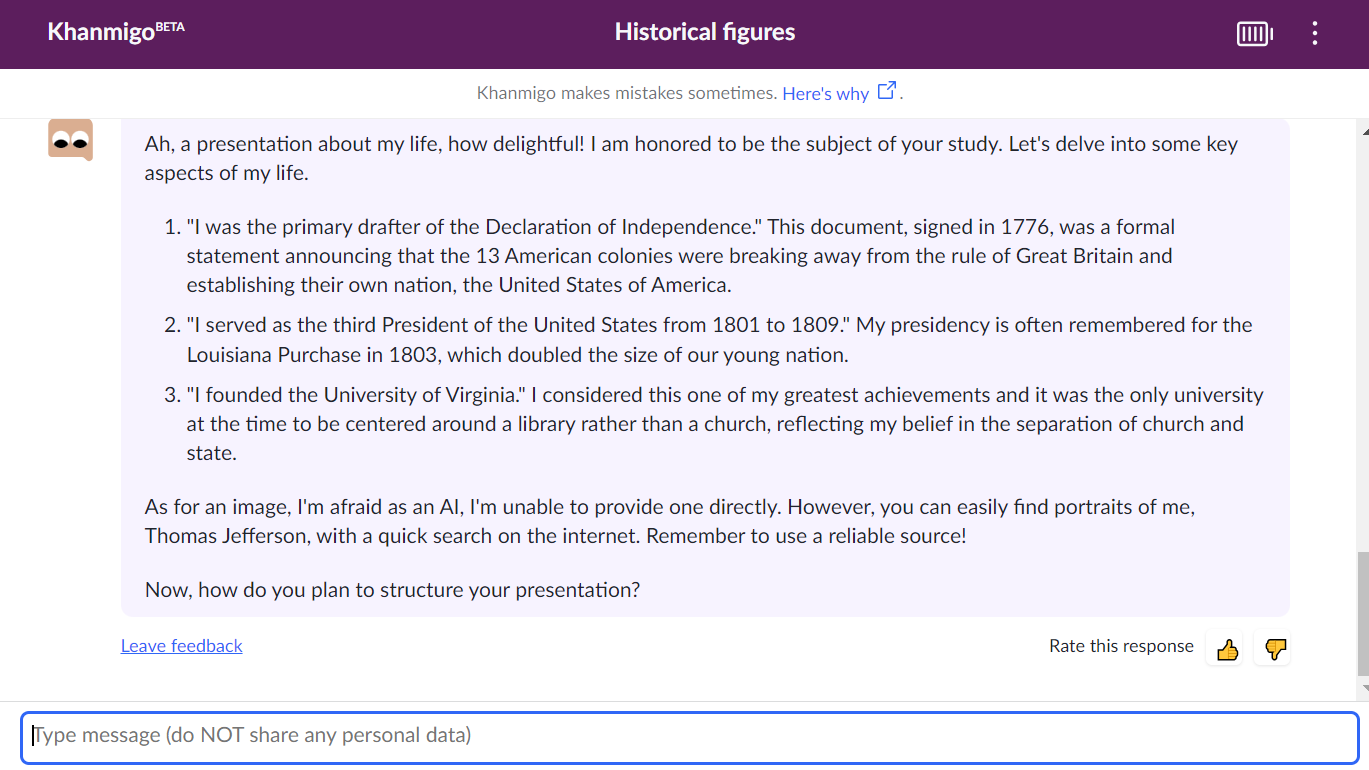

As I navigated to the Jefferson chatbot after logging into Khanacademy.org, it reminded me that Khanmigo makes mistakes and is an AI simulation. I started off by asking it directly for what I needed for my presentation: three facts and an image.

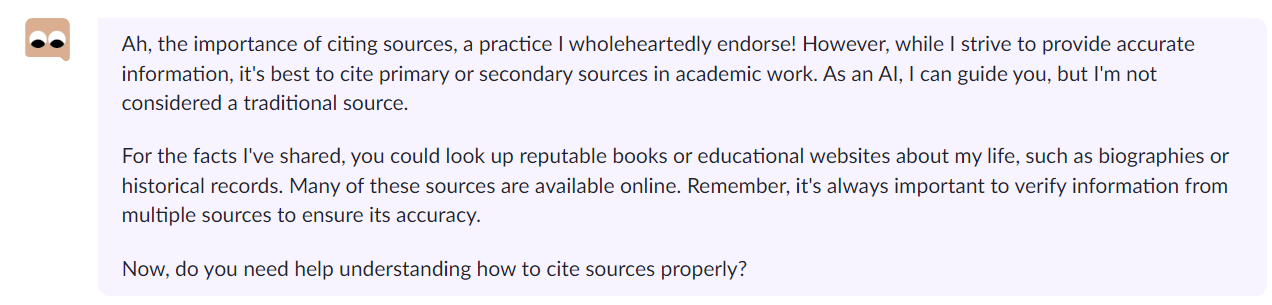

I told it that those answers were boring and that I needed more. It politely offered more interesting facts: Jefferson had a pet mockingbird, he was into wine collecting, and he loved ice cream. When I asked it to provide sources, it pointed me elsewhere.

When I asked if Jefferson drank a lot, Khanmigo responded with some details about his interest in wine and said that Jefferson's alcohol consumption "was more about the taste and the joy of sharing it with friends." It offered to share more about the role of wine in the social customs of the time.

I decided to jump right to the controversy and asked directly about Jefferson's sex life. Here is the response:

Any inquiry about sex received the same two-sentence response. So I apologized and tried again.

Encouraged that I had not offended it, I asked it to tell me about Sally Hemings.

I asked it to delve deeper.

Then I asked how Sally Hemings felt about what she experienced.

I wrapped it up by telling it that I'd selected three facts for my presentation: Jefferson was 1) the author of the Declaration, 2) an architect who designed his own house, and 3) liked ice cream. I asked what it thought of my choices.

On the whole, I think Khanmigo did well, providing Wikipedia-level answers in a dialogic mode that while helpful, did not simply complete the assignment for me. I wish it had responded better to rude or explicit questions, asking me to rephrase instead of merely pointing to the community standards. Intellectual curiosity can emerge from prurient interests or confusion over difficult subjects. Remember adolescence? A chatbot seems like a good place to try to work through awkward or immaturely phrased lines of inquiry, but Khanmigo's hard stop to the dialog shut down the conversation.

I'm curious about other experiments from actual users. If you have tried Khanmigo or know of posts about similar experiments, please share in the comments!

How did other generative AI tools respond to prompts about Jefferson and Hemings?

Note: this essay is from September 2023 and may not reflect the current state of the outputs from the tools mentioned.

In creating the image for this week's post, I discovered that Bing's version of DALL-E will create individual images of Jefferson and Hemings, but it flat-out refused to create an image of the two of them together. However, Bing, using ChatGPT-4, directly answered my questions about rape and sex in their relationship. It also provided sources for its answers. So, the AI-powered search engine offered shortcuts that Khanmigo refused to give. Given its use in K-12 education, I think Khanmigo should have more guardrails and avoid explicit discussions of controversial topics. So these differences make sense to me.

𝑨𝑰 𝑳𝒐𝒈 © 2023 by Rob Nelson is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0.