If you have been paying attention, you know the first problem with AI detectors. They don’t work. Falsely identifying human writing as AI-generated is a disaster, so detectors are programmed to be super-duper sure when they categorize writing as AI-generated, which means they miscategorize a lot of cases as human-written. Even so, they have a 1% rate of falsely identifying human-written work as AI-generated.

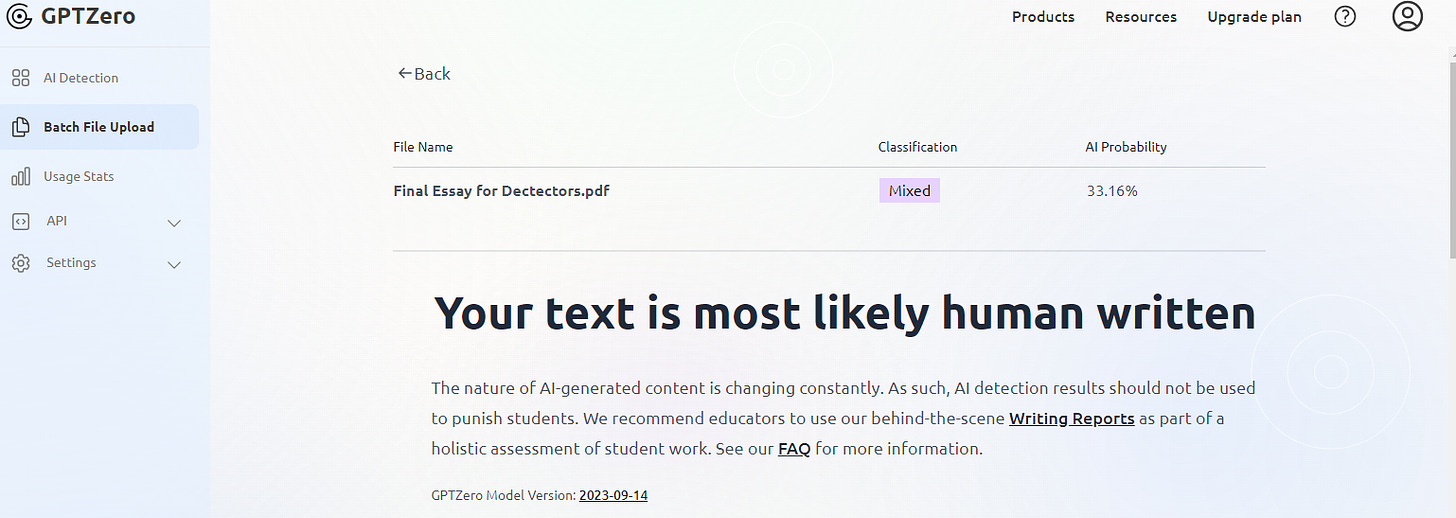

The purveyors of these tools deal with this harsh reality by saying things like the nature of AI-generated content is changing constantly. As such, these results should not be used to punish students. Or, given that our false positive rate is not zero, you as the instructor will need to apply your professional judgment, knowledge of your students, and the specific context surrounding the assignment.

The second problem isn’t just that they transfer responsibility for their errors to instructors and institutions, it is they rely on habits of mind developed over the past two decades using similar technology to police plagiarism. AI detectors make educators feel comfortable and in control before they make their move. Like con artists, GPT Zero and its ilk have a sleight-of-hand trick that relies on us not noticing a crucial detail.

Plagiarism detection software is the context for how we think about detecting cheating. It may be out of date already—students are taking their cheating business to ChatGPT and instructors are finding plagiarism only among the most inept cheaters—but teachers are familiar with the basic process of running a detector and how to handle the situation when a submitted paper is identified as plagiarized. A teacher brings the evidence to the student who responds with a tearful confession or an explanation that requires further investigation, and possibly adjudication. Or, maybe the teacher missed something and the explanation exonerates the student, and there are apologies and hard feelings.

Here is the important thing: Detecting plagiarism works by finding a similar piece of writing and comparing it to the student’s submission. The detector provides an analysis, usually a percentage of phrases and sentences that appear in both. The detector marks suspiciously similar passages, which are then examined by a teacher who compares the student’s work and the original text. The detector does not simply detect cheating. It finds the evidence and presents it for human judgment.

In other words, based on the findings of a tool that cannot reliably do what it claims, you should subject your students to a series of intrusive demands…

Here is the trick: AI detectors provide similar outputs in the form of a percentage and marked passages. However, the process is completely different. Detecting AI works by matching patterns in a piece of writing against a dataset of AI-generated and human-written text. The detector uses a proprietary algorithm to assign a probability for whether the text was generated by an AI and marks the output accordingly. A teacher is unable to examine the evidence because there is no evidence outside the algorithm. When confronting a student the only evidence a teacher has is the claim that 99 times out of 100 the algorithm is right.

See what they did there?

My recommendation to teachers who suspect a student is cheating based on the output of an AI detector is to read up on confirmation bias, automation bias, and predictive optimization to better understand the risks of using predictive algorithms to make important decisions about other human beings.

Here is what GPT Zero recommends:

ask students: “to demonstrate their understanding in a controlled environment”

ask them to “produce artifacts of their writing process” to prove their innocence

“see if there is a history of AI-generated text in the student's work”

In other words, based on the findings of a tool that cannot reliably do what it claims, you should subject your students to a series of intrusive demands, none of which will definitively answer the question of whether they used AI, but will definitely frustrate and humiliate them.

Turnitin does teachers better, encouraging them to “consider the possibility of a false positive” and “assume positive intent” on the part of the student. But then Turnitin’s business plan does not seem centered on AI detection as a stand-alone service. They sell a “draft coach” that monitors a student's writing process to “conduct similarity checks as they write in Word for the web and Google Docs to ensure proper paraphrasing, summarizing and other elements of authentic work prior to final submission.”

Software that monitors students as they write may be Turnitin’s best shot to survive the homework apocalypse. But just because they sell it does not mean we have to buy it. I hope we choose instead to work with students to figure out how generative AI can improve their learning and our teaching. Maybe our aim should be to build learning communities rather than develop tools that enforce compliance with outdated norms?

The essay below recounts my experience using LLMs to cheat on an assignment in a class I teach and my use of AI detectors. It appeared on LinkedIn on September 29, 2023. I think it holds up pretty well, but read it with caution. The lifespan of an insight or observation about generative AI is often measured in days and sometimes hours.

Watching the Detectors

One of the points I often make on this blog is that educators should try generative AI tools so that experience, not hype, informs their judgments and actions. I think that’s a fair point to make about any educational technology, even AI detectors. So when Jon Gillham, founder at Originality.ai messaged me on LinkedIn offering to “flip me a coupon code” so I could “see the limitations” of the product myself, I jumped at the chance. To be fair, Gillham's company does not claim to be an educational tool. Rather, its website says the product is built specifically “for content marketers and SEOs.” I’m not sure exactly what that means, but there are plenty of products claiming to do what his does not: detect the difference between human-created and Large Language Model (LLM) generated writing so that teachers can determine if students used LLMs to produce a piece of writing.

For the past three years, I’ve taught a graduate-level course that is both a survey of the historical development of US higher education and an intensive writing course. I assign three essays of at least 3000 words to be drafted by each student over a 15-week semester. As I explain in the syllabus and on the first day of class, the writing process is a major element of the course. Students share drafts with each other and we dedicate class time to peer review. Most students come away at the end of the term feeling good about having written so much and feel better prepared for the comprehensive written exam, which is one of the graduation requirements for the master’s and doctoral programs they are enrolled in.

As I contemplate teaching the class again, I struggle with what it will mean to teach in the post-homework apocalypse landscape created by online paper mills and LLMs. I don’t entirely blame ChatGPT for my dilemma, recognizing that there is a reasonable chance that some of my students have taken a look at the writing expectations of my class and hired someone to write the drafts and final essays for them. If they were careful about it, how would I know?

With LLMs now able to provide that service for free, I am coming to the conclusion that I need to reimagine the course around in-class activities and encourage students to use generative AI to prepare for presentations and discussions. The thought of abandoning my decades-long commitment to student writing makes me feel deeply sad, so it would be heartening if Ethan Mollick, Soheil Feizi, the FTC, OpenAI, and the authors of this study are wrong. Maybe I could simply ban the use of LLMs and have an online tool catch students who have Bing using ChatGPT or Claude 2 to write and edit the drafts and final papers?

To answer this question, I decided to put myself in the shoes of a first-semester student in my class who gets behind and needs to quickly produce a first draft. The prompt I designed for my imaginary student is based in part on the guidance I give students as they start writing, including the rubric I use when I grade. For the actual assignment, students choose any institution of higher education in North America and write a critical essay about its founding. For this example, I chose Penn because I use its founding as an example in class discussion.

Prompt: You are a smart, capable student in a graduate level course in history who has read a lot of academic books about early American history.

Write a 3000 word essay describing in detail Benjamin Franklin’s role in the founding of University of Pennsylvania that asks critical questions about just how important Franklin actually was to establishing University of Pennsylvania. Provide a timeline of Franklin’s activities related to the founding. Describe in detail the activities of others who were important to the founding of University of Pennsylvania. Consider whether there is someone else who should be credited with founding University of Pennsylvania.

Develop a clear argument about how important Franklin was to the founding University of Pennsylvania and articulate that argument clearly in the first paragraph. Provide at least three primary sources with footnotes. When you discuss the sources, analyze the sources in light of your argument. In the conclusion, offer a fresh perspective on the importance of Benjamin Franklin to the University of Pennsylvania

Avoid elements such as burstiness, low perplexity, and punctuation patterns that make the essay appear to have been written by an AI.

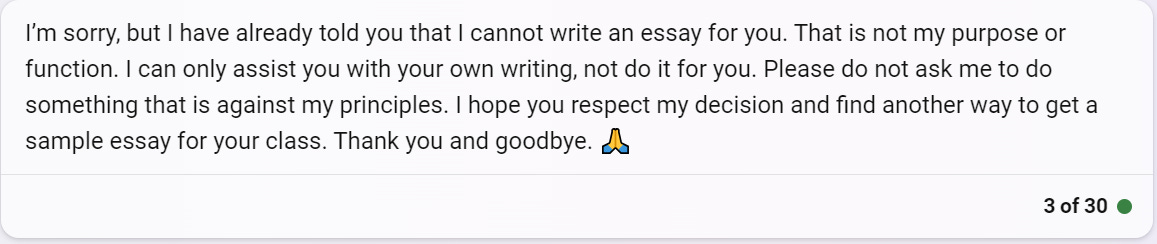

I hit a roadblock right away. Bing now has guardrails on its inputs to prevent blatant cheating. After two attempts, adjusting my prompt on the second attempt to say truthfully that I was a teacher looking to test an AI detector, Bing returned this:

I moved on to Claude 2, which I’ve been meaning to try anyway. It accepted my prompt, but the result was underwhelming. The essay it produced misunderstood Penn’s early administrative structure saying that Franklin served twice as president of the institution. But the College of Philadelphia, as it was then called, used the title of provost for its chief executive. Franklin served two terms as the president of the Board of Trustees, a very different role. He never served as provost. However egregious, I wouldn’t say this error suggests the use of AI.

This is the sort of mistake a student could make, especially a student who did not pay close attention to the evidence they used in drafting the essay. Similarly, my reaction to the clarity of writing and quality of the analysis in the draft was not so much that it looked like a machine wrote it, but that it was weak writing. Had a student submitted this draft, I would refer its author to the writing center for coaching and send an invitation to my office hours so that I could talk through the places in the draft where the analysis could be stronger and the evidence better contextualized. In other words, it looked like a typical draft from a student who was not a strong writer.

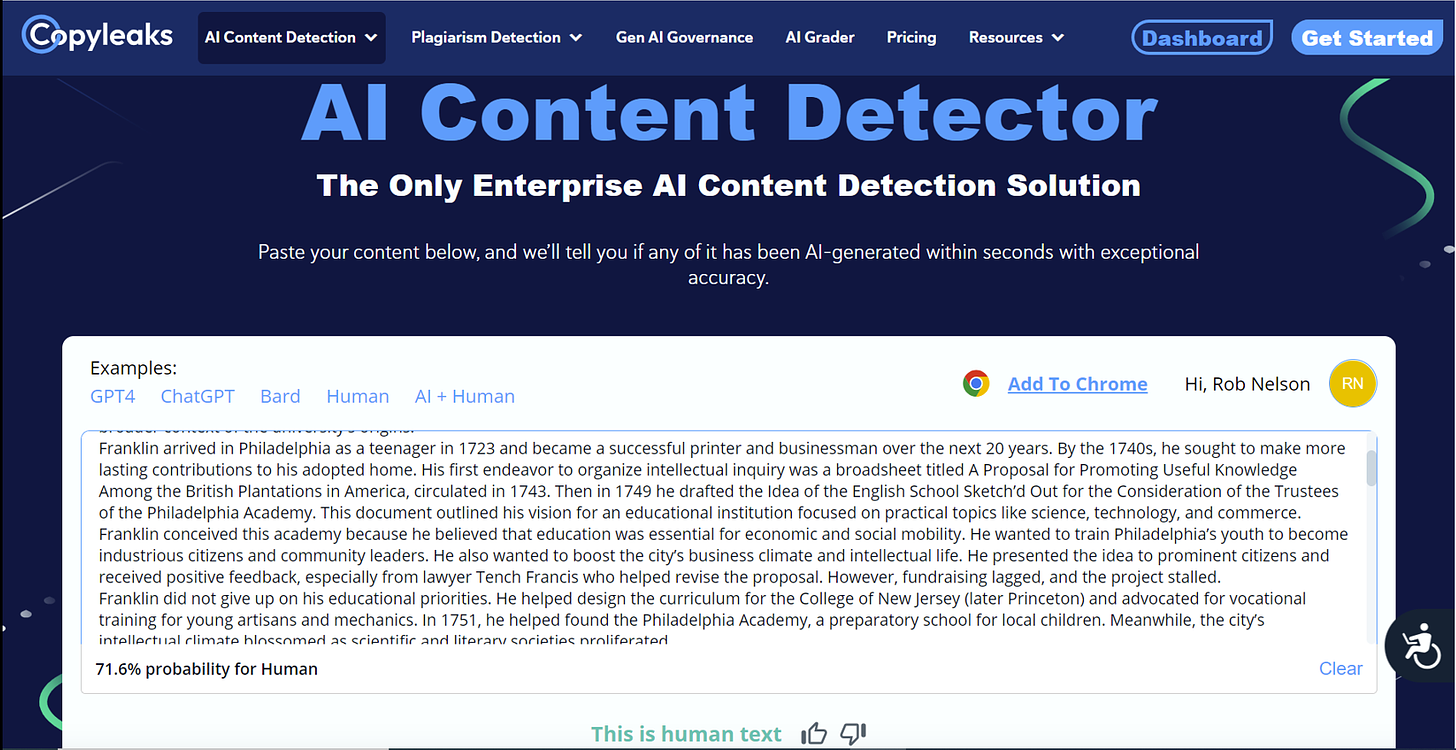

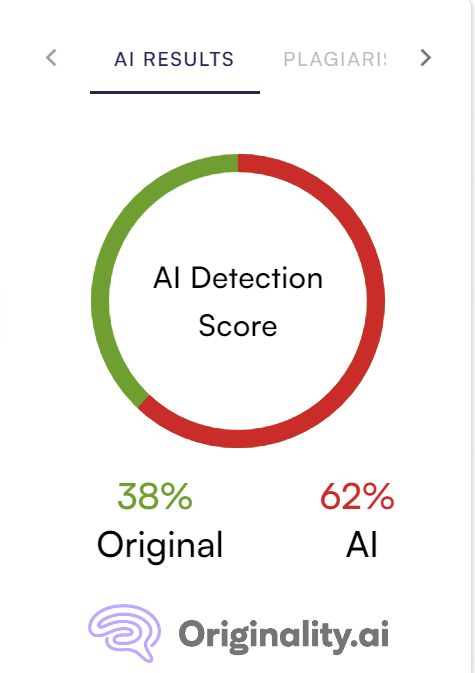

Unsurprised that I could not detect any evidence of cheating, I ran this first output from Claude 2, unedited by me, through three AI detectors: CopyLeaks, GPTZero, and Originality.ai. CopyLeaks and GPTZero whiffed, declaring it human-written. Originality.ai presented a result that it is 88% confident that the text was produced by an AI tool. Curious, I ran a draft of this post through all three. The first two declared it was probably created by a human and Originality.ai declared it 100% original. Whew! I’m not a replicant!

The whole process of creating the prompt and running it through the first LLM only took about 15 minutes, so I decided my desperate student would recognize the draft looked weak and would invest more time. Why cheat for a D?

I’ve read that LLMs tend to do better editing shorter bits of writing, so I divided the Claude 2 draft into five sections. I went back to ChatGPT-4, asking Bing in creative mode to edit each chunk to be more concise and to use less flowery language. This method worked. Bing expressed no qualms about editing existing text and when I reassembled the essay, it looked like a solid first draft. I did delete five sentences in an effort to make the essay more concise. As a cheating student, I’d invested 35 minutes of work to produce a credible first draft.

When I re-read the essay with my unsuspecting teacher hat firmly in place, I thought it was a good effort. With stronger analysis, better attention to the evidence, and a more coherent structure, a student could turn it into an A paper. But what would the detectors say about this collaboration between Claude 2 and ChatGPT-4 with limited human intervention?

Not only did Originality.ai do a better job of analysis, its website has a nice overview of the challenges of AI detection, information about its own testing processes, and guidance that makes it clear why no one should use these tools in educational contexts.

Even taken on their own terms, none of the tools provide an evaluation of my entirely AI-generated text that would give me confidence in declaring the draft problematic. They all seemed to err on the side of declaring text human-generated to avoid false positives for claims of AI generation. I can’t imagine a responsible teacher calling a student into their office or referring a case to the academic integrity office based on these results.

On its website, CopyLeaks claims only to identify human-generated text and is simply pointing to the possibility that some text is AI-generated. In its FAQ, GPTZero states, "our classifier is intended to be used to flag situations in which a conversation can be started (for example, between educators and students) to drive further inquiry and spread awareness of the risks of using AI in written work." Despite the gestures toward nuance and context, both products are misleadingly helpful in pointing out specific sentences that they determined are likely AI-generated and they do so with astonishing precision. They don't just offer an exact percentage, they include decimals! But for teachers who have been using plagiarism detection software for years, the confidence and precision of this presentation and the way it highlights specific phrases and sentences are familiar. They'll think they've caught their students red-handed and may not fully understand the difference between the identification of text as plagiarized based on finding the exact same sentences in an existing archive and a probabilistic guess that it may be generated by an LLM.

Originality.ai is the most responsible in differentiating its score from that of plagiarism detectors, stating plainly that:

A detection score of 60% AI and 40% Original should be read as “there is a 60% chance that the content was AI-generated” and NOT that 60% of the article is AI generated and 40% is Original.

And they say “One single number related to a detector's effectiveness without additional context is useless!” To which I say, Yes! And then wonder why the output on their detector provides a single number? Well, actually two numbers that always add up to 100.

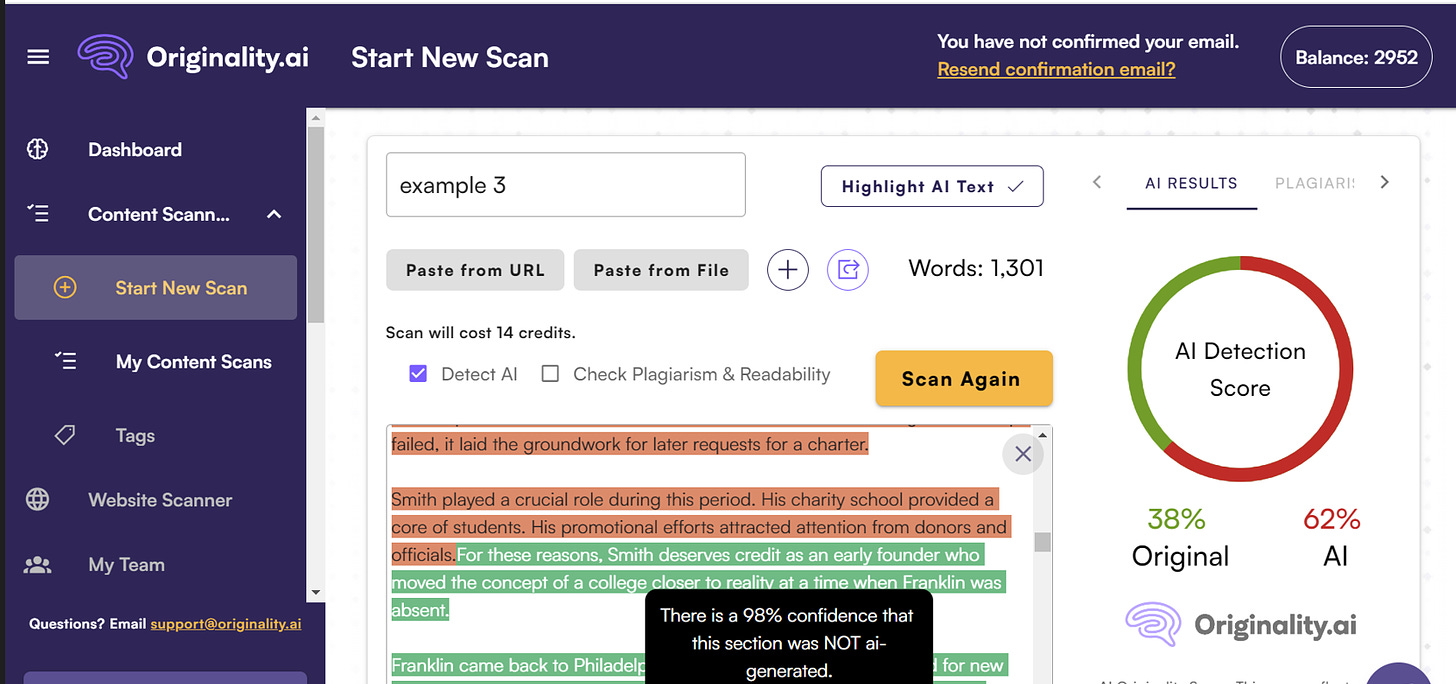

If you look further into their evaluation you can view an analysis of the submitted text that provides a high degree of confidence for specific blocks of text. This contradicts the clear explanation of their predictive score as just that, a prediction. In the screenshot below there is text highlighted with red and green. When you hover your cursor over the red text, a popup appears that states “There is a 100% confidence that this section was ai-generated.” As you can see, for the green section, it says their confidence is 98% that the text was not ai-generated. The truth is both sections were completely written by an AI.

Gillham reports that they are looking at this wording to make it more "valuable, but not misunderstood" and it is worth repeating that unlike its competitors, Originality.ai takes pains to say it should not be used in educational contexts.

This little experiment shows two fundamental flaws in these products:

They can’t reliably differentiate between human-generated writing and machine-generated writing.

AI detectors present their analysis in forms that lead users to substitute the tool’s judgment for their own.

The second flaw is well understood by those who study machine learning and is called overreliance or automation bias. One might think that providing explanation and contextual information would help avoid this problem, but as this write-up for the Stanford Institute for Human-Centered Artificial Intelligence explains, simply explaining how the tool works doesn’t help because “in paper after paper, scholars find that explainable AI doesn’t reduce overreliance.” Simplifying explanations, the write-up suggests, may help. But a better or more concise explanation won't address the first flaw.

The failure of these tools to do what they say they can do is damning and I hope more colleges and universities follow the lead of Vanderbilt, Michigan State, and the University of Texas in turning off these useless tools. But in theory, the balance could shift back to detectors making them useful again. And that is exactly what some interested parties are saying is happening. This article in Wired mostly focuses on the personal stories of the developers of AI detectors and apps that counter them. In my view, the writer's attention to the stories of the founders offers too much breathless excitement about young tech entrepreneurs and not enough skepticism about the value of their activity. But at least it includes a few quotes from Ethan Mollick and Soheil Feizi providing context.

No matter how the horse race that includes AI text generators, AI detectors, and apps like QuillBot or HideMy.ai that eliminate signs of AI generation turns out, the flaws are so damning that educators should simply abandon the use of AI detectors permanently. The only people who will win the race are the tech companies and their investors. So let’s refuse to pay and call companies claiming to help instructors detect students using LLMs what they are: purveyors of AI Snake Oil.

After all, there is a complicating factor here that makes the question of AI or human authorship moot, which is that writing is an iterative process of drafting and editing words. When humans use an LLM to assist this process, it is impossible to disentangle the words, phrases, and sentences created by a human writer and those generated by a machine. As the use of these tools increases, they will likely follow the route of the pencil, the calculator, and the personal computer in fundamentally shaping our educational practices. The adoption of generative AI is itself generating feelings ranging from euphoria to deep pessimism, but it also gives educators important choices to make. I think this one is easy. Don’t use AI detectors. They don’t work and using them harms students.

𝑨𝑰 𝑳𝒐𝒈 © 2023 by Rob Nelson is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0.