Disclosure: Since I mentioned Leepfrog Technologies in this essay, I need to tell you that I am working with them on AI strategy and a few other projects. Everything on this blog is written independently of my work as a consultant, but I try to be transparent about how I earn a living. See my disclosures page and this essay for more on that topic.

It has never been this bad

Being a historian has given me a bad habit. When someone talks to me about how things are terrible and awful, I respond with a time in the past when things were worse. It is an irritating way to respond to someone who just wants to commiserate.

If you say, “Gosh, COVID-19 was terrible and awful,” I’ll come back with, “You think that was bad? Let me tell you about 1918 when we had a global pandemic during a world war.”

Say something about how close and terrible the outcome of the last election was. I’ll give a mini-lecture about the election of 1876, which was marked by state-level electoral fraud and widespread voter intimidation, had the highest voter turnout in American history, and was decided by Congress. The compromise they came up with rolled back the freedoms and rights enshrined in the 13th, 14th, and 15th Amendments and brought an end to most forms of federal support for formerly enslaved people and their children.

My bad habit is driven by a professional obligation to tell anyone I can that there is no golden era we can get back to, never a time when things felt great as they were happening. Plus, I find it reassuring to say that whatever crisis we face, whether constitutional or educational, we have been through worse.

I don’t know yet about the political events of the past month. It seems bad, but it is hard to say how bad it is because its badness is masked by a lack of clarity about what it means to control the federal government’s computer systems. Does running the computers mean you run the government? In this footnote, you’ll find some places I go for answers.1

It is clear to me that when it comes to higher education in the US, it has never been this bad. How can I say that with confidence? Why can’t I indulge my habit of contextualizing present badness with stories of badness past?

Over the past one hundred and fifty years, we, the people, have built the most powerful set of institutions for creating and disseminating knowledge in the world. The reason it has never been this bad before in US higher education is that we have never had so much to lose.

COVID-19 wasn’t as terrible as the global pandemic of 1918 because there were significant advances in biomedical research on influenza and a research infrastructure in place to understand the virus and develop a vaccine.

The damage done to human rights and human beings by ending Reconstruction in 1877 was mitigated, in part, by slowly expanding educational opportunities, first through women’s colleges and HBCUs and then a slow, steady expansion of institutions admitting formerly excluded groups. Our system of higher education, as imperfect as it has been, was giving just about anyone able to learn a decent shot at graduating college.

AI is not happening apart from the ongoing and illegal interference with funding the NIH and the Dear Colleague letter issued on February 14. Exploring the value of generative AI in our work as teachers, students, and researchers is taking place as the federal government destroys ambitious projects to create knowledge about cancer treatments. Administrators are evaluating the risks and opportunities afforded by this new cultural technology as the government attempts to wipe out campus programs that use specific language to describe what they do.

Technological change is social change

That was how I opened a talk I gave at the Leepfrog User Conference in New Orleans last week. Like all my talks on AI, this was a discussion of the audience’s ideas and experiences involving the new technology. I started off with those grim observations to make a point that often gets overlooked when talking about AI. Technological change happens within a social context. Figuring out a new technology—how to use a new tool and for what— is part of social and political life, not something separate from it.

The conference gathers academic administrators who manage curriculum and other academic processes. Because I was one for so long, these curriculum geeks, academic operations staff, and educational technologists are my community within the larger community of higher education. I love hanging out with people who love solving the problems of educational bureaucracies. They are my weird and wonderful tribe.

Last year, the group was trepidatious about what the AI future would mean for them. When I asked how many had used something that they considered artificial intelligence, only a few raised their hands. This year, everyone in the room did. Last year, there were a few tentative experiments with using LLMs to assist in generating marketing materials or copyediting emails. This year, I talked to dozens of people who were coaxing Copilot to automate aspects of reporting or using Claude to do things like generate preliminary transcript evaluations for faculty to review and approve. When I asked questions about risks or challenges, their answers were considered and careful.

For all the stories of academics burying their heads in the sand about AI or racing to the barricades to fight everything AI at all costs, my fellow bureaucrats and technologists are doing the work we have been doing since digital tools built using electronic computers and the internet first became available: figuring out the value of new technology for managing higher education. The emerging consensus, which I heard expressed throughout the conference, is that AI has the potential, if used carefully and responsibly, to help manage the complex bureaucratic machinery of higher education.

Learning about how to apply AI to higher education administration would be a challenge in the best of times. Today, the stress on that machinery and the people who run it is tremendous. The staffing freezes and reduction in PhD admissions announced these past few weeks are the start of something worse. Institutions will reduce the number of people on campus who are familiar with generative AI tools just as that knowledge becomes more important.

Digital transformation redux

The hype about how AI will create efficiencies combined with reducing the level of human expertise on campus is a giant trap hidden in plain sight amid all the turmoil and chaos. The recent history of educational technology is a story of vendors and consultants hyping “digital transformation” and institutions buying that hype, literally. Institutions of higher education, along with every other form of large bureaucratic organization, increased their spending on IT out of fear of missing out on the great benefits of networked personal computing and IT infrastructure.

Decision-makers, and I was one of them, believed institutions would save money through the efficiencies that would surely follow. The past twenty-five years have taught hard lessons about locking our academic processes into specific products and services. Turns out, many of our partners who were so focused on client success and user growth ended up in the hands of private equity, who didn’t care about anything other than extracting as much value from their investment as possible in the shortest time. “Would you rather pay a 15% increase in your annual licensing fee or start a multi-year project to implement an alternative?” was a question no one saw coming.

It wasn’t just the vendors getting sold to private equity and then raising prices. The promised efficiencies never materialized. Look at how much IT staffing had to increase to solve the problems of data integration, data security, and privacy that digital tools created. We can debate whether the investment in digital tools that transformed how we work was educationally valuable. Most days, I would say yes, but not by a lot. But no one can credibly say that the transition to digital systems run by Microsoft, Google, and hundreds of other companies saved institutions of higher education money.

This is well understood by the bureaucrats who manage these systems. But given the excitement on some campuses about the unrealized magic possibilities of AI, I worry that executive leadership, pressured by their boards, will buy the same hype all over again. This time about AI. Without understanding the social and technological context, the difference between paying a living wage (plus benefits!) to a human and $200 dollars a month for AGI (It’s coming, right? Everyone seems so sure.) seems like something a responsible leader has to consider.

My skepticism about AI is often cast within a frame of humanism, of valuing human effort because it is human. But there is a strong case to be made for human labor in terms of managerial economics. Digital transformation was sold on the promise of returns on investment through productivity and efficiency gains. There were no actual savings to be had then, and there won’t be in the transition to AI. Even if the enthusiasts are right about how many problems AI will solve, new ones will be created that will be solved only through human expertise. Even if, by some miracle and a lot of human effort, we figure out how to use AI to reduce costs in the next five years, vendors will raise the price to ensure they get any savings.

Here is my advice for higher education executives facing the unprecedented challenges of the coming years: invest in your people first and the technology only to the extent you can afford it. If you purchase AI products, you need staff to make sure you do it right. They can help you implement it carefully and with an eye on your nearest exit. They will make sure any vendor selling AI can explain to you how their product arrives at its outputs and how they protect institutional data.2

Taking care and thinking critically doesn’t mean you are ignoring AI. It means you are building your organizational knowledge about how it works and thinking about AI in relation to what’s happening on your campus, in the nation, and in the world. It’s bad out there. Let’s not make it worse.

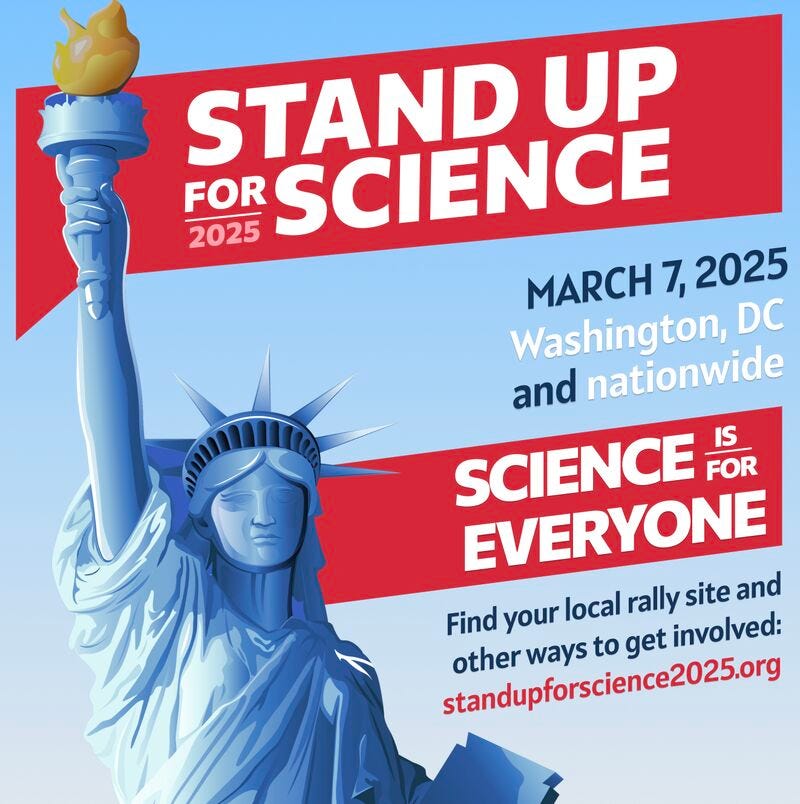

I don’t have any good ideas for what to do about how bad things are in Washington, but I believe standing up for what we believe is important. I will be at the Stand Up for Science at Philadelphia City Hall this Friday, March 7, at 11am ET. Get in touch if you want to meet up there.

AI Log, LLC. ©2025 All rights reserved.

Paul Krugman is as essential today as he was during the 2009 financial crisis. His interview with Nathan Tankus will help you understand what’s happened with the federal government’s computer systems. His interview with Jim Chanos will make you smarter about AI hype and markets.

Reading Jennifer Pahlka, author of Recoding America: Why Government Is Failing in the Digital Age and How We Can Do Better, is helping me think about what we actually need, along with what is happening when it comes to improving government computing systems.

Brad Delong presents relevant advice from Martin Mycielski about surviving authoritarian regimes and a reminder that we must ground ourselves and others in reality when facing lies and doublethink.

Underground Empire by Henry Farrell and Abe Newman describes the larger context of relatively recent changes in global information systems. I happen to have this book on my shelf because I automatically buy books written by bloggers I admire, and Henry Farrell is one of the best on the social and organizational contexts of AI. Underground Empire has been essential to my understanding of how the things that are happening are happening.

One lesson of the past twenty years is that getting it in writing that a vendor will protect your institutional data doesn’t mean much. When something goes wrong, courts and angry lawyers don’t fix the problem. An apology and a penalty payment, even if the company is around to offer them, will just be a distraction from cleaning up the damage.

With most AI companies moving so fast, you should not take a vendor’s willingness to sign an agreement as a sign of their integrity or ability to do what they say. There is no reason to trust an AI start-up, including one worth billions and billions of dollars. In their risk assessment, their company will either be gone, or a million-dollar penalty will be a drop in their revenue bucket.

Verify. Ask questions. Have every vendor explain exactly what they are doing with AI models and how they see the risks of using them. If they can’t explain because it’s proprietary, then sign an NDA so they can explain it. If their lawyers say they can’t offer an NDA, then walk away. Why trust a company that doesn’t trust you?

Thanks for this, Rob. Context is King, and you’re offering a valuable perspective for all university human improvement workers. Hobb’s Leviathan has been quietly moving through the depths, preparing for this Trumpian moment. I’m not prepared to comment on your comparison between 1877 and 2025 in terms of which is more bad, but you’ve powerfully captured an angle on where we are by way of the comparison. It IS bad. The advice to university admin to draw on local experts and give them the tools and time the campus can afford to begin the integration work is sound. Readers ought to share this post widely among the admin types they know. Your experience as one of them with a voice of reason is sorely needed. Nice work!