Disruption is the wrong word for what's happening with generative AI

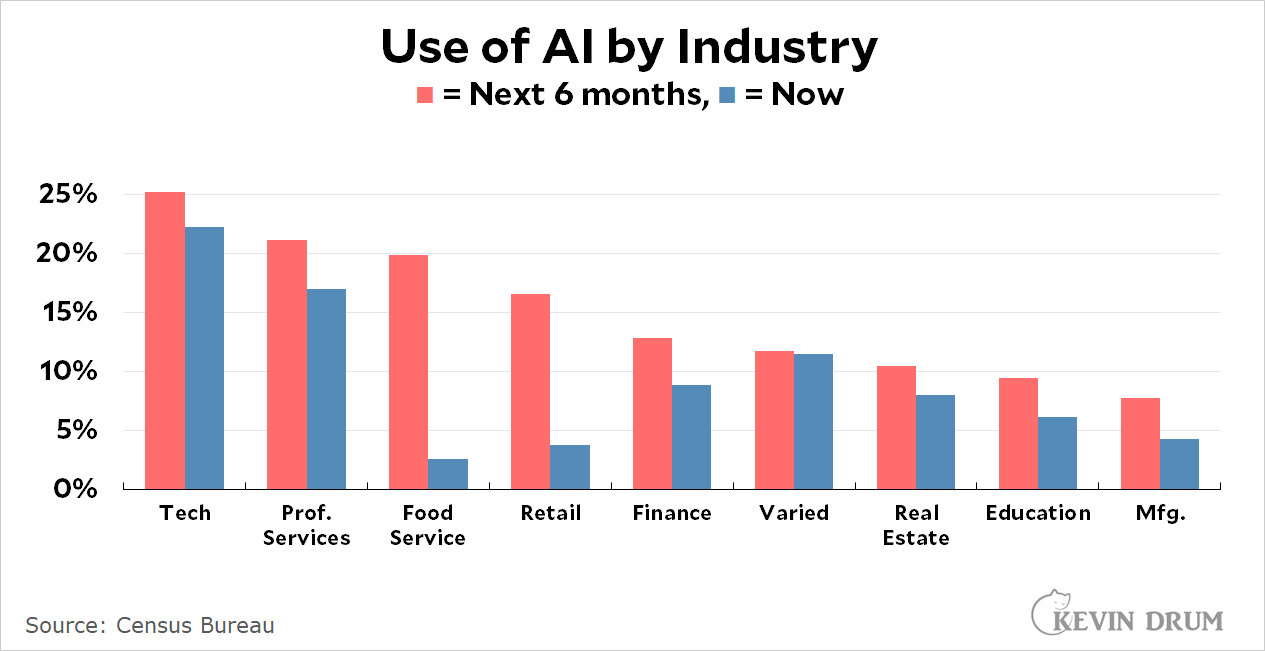

Snapshot from Census Data on the use of AI by businesses

Given the volume of hype around AI, much of it from those selling something or looking to monetize clicks, it is nice when high-quality public data about the new technology is released. Here is a Census Working Paper (Working Paper Number CES-24-16).

The paper mostly confirms my prior assumptions, which is probably why I am excited to share. Some of its findings are that so far, no mass replacement of workers is underway and that some adoption (1 out of 7 users plan to stop using it) is short-lived, “potentially indicating some degree of ongoing experimentation or temporary use that may result in de-adoption.” Whatever is happening with the actual adoption of generative AI it is not happening quickly. That said, there are measurable impacts that suggest the use of generative AI makes firms more productive, at least as indicated by what businesses have to say in response to government surveys.

One limitation is that the survey does not tell us much about how these businesses use AI or how much of it is generative AI. The question defining the term is: did this business use Artificial Intelligence to produce goods or services? (e.g., machine learning, natural language processing, virtual agents, voice recognition, etc.). So maybe all that’s happening is that businesses are using Alexa to order from Amazon? Given the recent Pew Research Center result that “about one-in-ten adults who have heard of ChatGPT and are currently working for pay have used it at work,” I think it is safe to assume we’re talking about generative AI here.

Some key sentences from the report:

Our findings are consistent with the view that, although AI has been under development for some time with rapid advances in recent years, AI use by businesses remains in relatively early days.

AI use, while especially high in the largest firms, has a U-shaped pattern with respect to firm size…[this suggests] that some AI applications (e.g., Generative AI) may be general purpose technologies that do not involve large fixed costs making it more attractive to young and small firms.

AI-using businesses generally perform better than non-users and expect to do so in the future. They also more commonly experience employment expansions than contractions compared to non-users. The overall better performance of AI-using businesses is a fact that has repeatedly emerged from the analysis of other data, including data from the ABS [Annual Business Survey] and the BFS [Business Formation Statistics].

Note: these are other Census.gov reports.

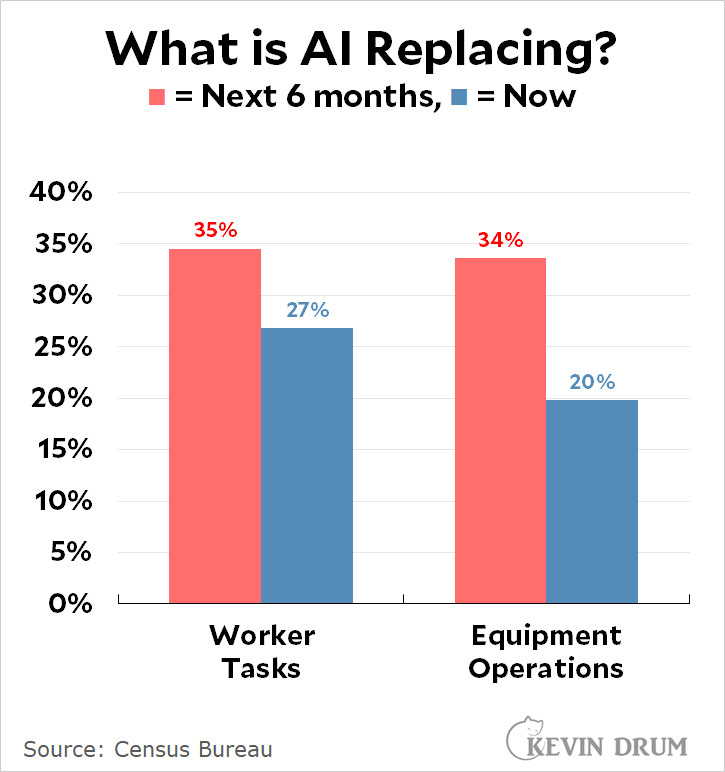

Kevin Drum is one of my favorite bloggers primarily because he makes a habit of turning public data into excellent charts. See more here. Drum thinks the chart above indicates that workers are going to be replaced, but I am not so sure. In some industrial production, automation does produce that result, and overall creates new, but different jobs. Automating knowledge work may not work the same way.

The disruption machine is still going strong

My use of the word "disruption" in the title of this note reminded me of Jill Lepore's essay The Disruption Machine from 2014. Ten years later it feels relevant as an antidote to overexcited writing about how generative AI is changing everything, everywhere, right now.

The book referenced below is The Innovator's Dilemma: When New Technologies Cause Great Firms to Fail (1997) by Clayton Christensen. The book and its sequels are responsible for many of the delusions that inform the hype about disruption as it relates to the adoption of generative AI. Here’s Lepore:

Ever since “The Innovator’s Dilemma,” everyone is either disrupting or being disrupted. There are disruption consultants, disruption conferences, and disruption seminars. This fall, the University of Southern California is opening a new program: “The degree is in disruption,” the university announced.

There is still a disruptive innovation minor at USC's Iovine and Young Academy.

Most big ideas have loud critics. Not disruption. Disruptive innovation as the explanation for how change happens has been subject to little serious criticism, partly because it’s headlong, while critical inquiry is unhurried; partly because disrupters ridicule doubters by charging them with fogyism, as if to criticize a theory of change were identical to decrying change; and partly because, in its modern usage, innovation is the idea of progress jammed into a criticism-proof jack-in-the-box.

Lepore shows that Christensen's methods for showing how disruption works do not always hold up under scrutiny and his conclusions are founded on a theory of change that he assumes rather than demonstrates through historical analysis grounded in sources.

Christensen’s sources are often dubious and his logic questionable. His single citation for his investigation of the “disruptive transition from mechanical to electronic motor controls,” in which he identifies the Allen-Bradley Company as triumphing over four rivals, is a book called “The Bradley Legacy,” an account published by a foundation established by the company’s founders. This is akin to calling an actor the greatest talent in a generation after interviewing his publicist. “Use theory to help guide data collection,” Christensen advises.

Lepore's takedown of Christensen's The Innovative University (2011) is especially interesting in light of the past year's disruptions of higher education, both those related to AI and to university governance.

The whole thing is worth reading.

𝑨𝑰 𝑳𝒐𝒈 offers links, analysis, and reflection on developments in AI and education. To receive each post in your email inbox:

To receive a notice in your LinkedIn feed, click here.

Learn more about AI Log here.

𝑨𝑰 𝑳𝒐𝒈 © 2024 by Rob Nelson is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0.

That Lepore essay was (and is) *such* a blockbuster.